By Nabilah Said and Corrie Tan

(5,950 words, 20-minute read)

Spoiler Alert: This text contains spoilers for The Coronologues: Silver Linings by The Singapore Repertory Theatre and Long Distance Affair by Juggerknot Theatre Company and PopUP Theatrics.

To view this text in its entirety, please read on a desktop.

Introduction (Nabilah)

It felt like there was a collective intake of breath as we waited for The Coronologues: Silver Linings to start. Part of that was imagined, since we were all watching from the privacy of our own homes, forced into physical separation because of COVID-19, but part of it, I think, was the shared sense of the momentousness of the occasion. This showcase by the Singapore Repertory Theatre, which premiered on May 26 live on Facebook, comprised the first nine original works from Singapore that would respond to our times; their presentations would represent the first glimpses of new ways of working and presenting work, predominantly achieved with the help of, and through, technology.

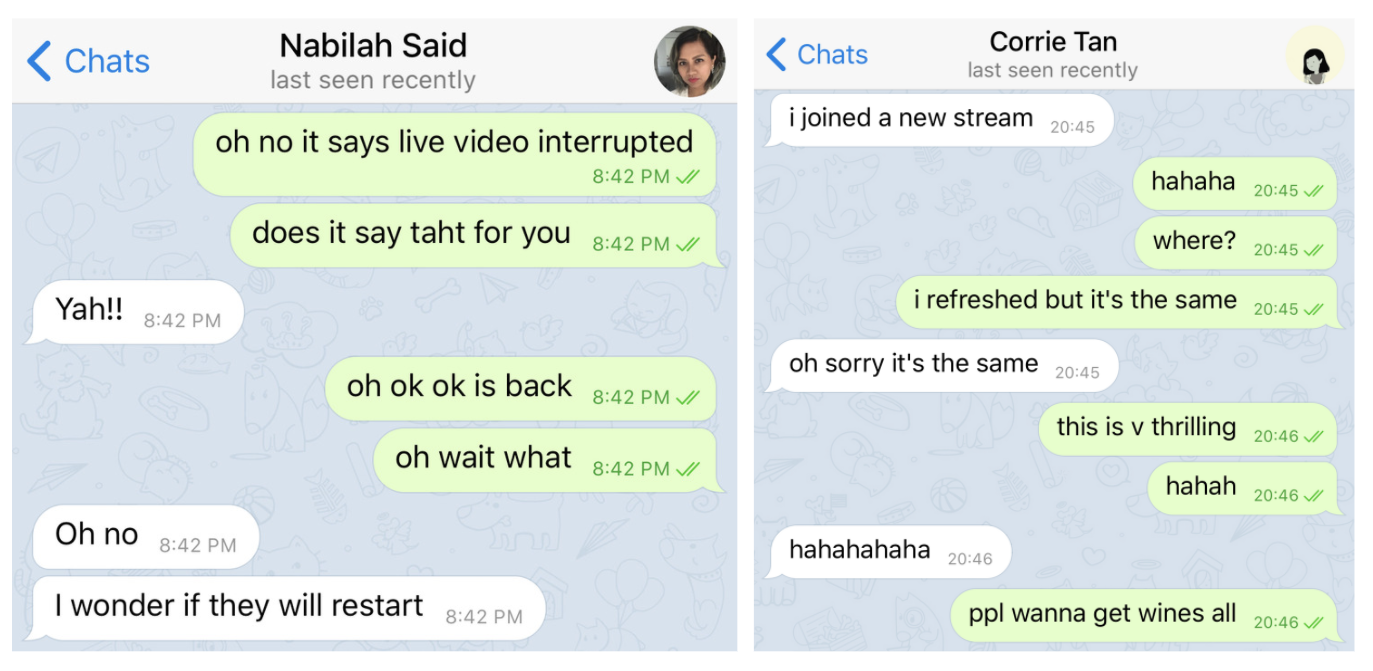

This new spectatorship is an active one. It requires hyperfocus and a sharp questioning of our senses. Even within the confined boxes of the video we’re watching, there is a barrage of signs to be read, misread and overread. Is that part of the set design, or is that just how their house is? Wow, look at his beard! Is that Jo Tan singing? (Yes it is!) The performances and writing add on even more layers: on top of the general excitement goes on laughter in response to a quip or an unexpected costume reveal, sudden sadness at the vulnerability of a character, delight at the sheer ingenuity of a line. Even a moment of technical difficulty can inspire a sudden flurry of excitement and new camaraderies in the chat.

Image: Corrie and Nabilah figure out/freak out over live stream technical difficulties on Telegram.

We all know that a piece of theatre is not complete without its audience. In watching a play presented in this time, there is a need for audiences to reassess and recontextualise their behaviours, effectively discovering a new kind of audienceship. While in the before times, phones were dutifully put to silent at the behest of a recorded pre-show announcement, now audiences can comment and verbally respond during the show in the chat section. Since the nine monologues had been pre-recorded, in some instances the theatremakers themselves could comment on their work or respond to the audience (Neo Swee Lin commented “Cameo Lim Kay Siu 🙂” during her performance of Work/Home Balance by Jacke Chye) We can’t change what happens in a pre-recorded, pre-set performance, which is the mode of presentation of Coronolagues, but with a live screening, we sure can make our presences known in the comments section.

A critic is not spared from this adventure of discovery. As we are learning how to be a new kind of audience for pandemic theatre, we also have to learn a new form of reflexivity. But like everyone else, our attention is not a loyal one – while watching a piece of theatre online, we are simultaneously worrying about being in a crisis, about how other people are doing, about the existential dread we feel in our bones, about the survival of the arts in Singapore, about rights and riots that are on the other side of the world but also on our doorstep. And then, there is the calibration of a barrage of emotions. Corrie and I were so overwhelmed by all our ~feelings~ that we had to get on Zoom afterwards to process them. This was a learned response – since the circuit breaker started, we have been participating in group Zoom chats with friends as a kind of post-show discussion space, which quickly turned into a decompression space. After watching Complicité’s The Encounter, for example, we sat in our respective rooms, some of us in darkness, our verbal thoughts punctuated by silences in equal measure.

Image: Nabilah and Corrie in a Zoom decompression call after watching “The Encounter” by Complicité online.

Our chat was nourishing, and yet, everything also felt scary and big. Essentially, we are trying to answer the question: what is the role of the arts critic in a pandemic? The spoiler alert is that we don’t know. The rules of reviewing have to be rewritten, and interim vocabularies (a term intimacy director Ann C. James uses in this discussion) have to be found. This started out as a response to Coronolagues; it’s now grown into a different kind of creature. We’ve decided to write about this work, and other works that we’ve encountered, as an assemblage of thoughts and impulses that emerged in the days following. This, we feel, would honour the fragmentedness of our thoughts, and frenetic stillness of our times.

28 May, Thursday, before dinner / 4 June, Thursday, before lunch (Corrie)

It was quite exciting to pull up a seat in front of the computer for Coronalogues, waiting for the placeholder image on the live stream to flicker to life. On my laptop screen, I’d tiled my various chat and messaging platform windows where at least a half a dozen friends were texting me throughout their watching experience – sharing fragments of lines that had resonated with them, or sharp and immediate emotional responses, from laughter to gasps and exclamations.

Image: Telegram exchange between Nabilah and Corrie featuring a punchline from Rishi Budhrani’s “Avocado Oil”, delivered dryly by Sharul Channa: “There are no psychopaths in Siglap.” Nabilah and Corrie are both die-hard easties, and they agree.

While tracing their arc of these nine monologues through the evening, we found ourselves sitting with some of the thematic concerns not just of the content of the pieces, but of the entire experience of spectatorship. I think we were also tying together (or perhaps unravelling) threads from previous experiences of watching shows and attending events online together. I wonder if we might see the same threads running through our other virtual encounters with performance both in content and form.

The first thing we alighted on was intimacy in a period of forced separation. The Coronalogues foreground all kinds of intimacies. There’s an excitement about exploring romantic relationships – both the endings and the beginnings of these relationships. A zoologist (performed by Andy Tear) makes a desperate plea for his off-screen wife, Shona, to return to him, and we watch him self-destruct as the lockdown wears on. A woman (Sharul Channa) who’s about to resign herself to an arranged marriage in Boston finds escape when borders close, and she meets a handsome stranger in a supermarket when they both reach for the same bottle of avocado oil. She meditates on her newfound focus on the eyes of strangers – echoed in the final monologue of the evening where another woman (Bridget Fernandez) falls in love in another supermarket meet-cute: with a man with “the softest eyes I had ever seen”. But these intimacies aren’t just romantic: they’re also embedded in the gestures of performance and cinematography. Most of the pieces are confessional, confiding – and contain incidental moments of private connection rendered public. A man (Wheelsmith) sits in the darkness of his room, and we catch a glimpse of moments of prayer, his connection with the divine. While a well-dressed woman (Neo Swee Lin) discusses working from home in front of the camera, her husband (played by Neo’s real-life husband, Lim Kay Siu) ambles behind her, half-dressed – and we later also find out that she’s only well-dressed from the waist up, and in cute pajamas from the waist down. Beyond these choreographed intimacies, there’s the strange line we tread between reality and fiction, how homes and set pieces are framed – and what we read into the carefully framed domestic spaces of each character when we recognise that these are also mini expeditions into the homes of their performer (guilty: one of my messages to Nabilah did in fact read: “WHERE does ______ stay??”).

It makes sense to me that we’re all greedy for these kinds of intimate connections – the Coronalogues’ focus on intimacy runs alongside a perhaps more visible thread of isolation. Wheelsmith’s monologue, in particular, surfaces questions around disability, discrimination and confinement during a period of hyper-restricted mobility, and how the pandemic might be a great leveller. He writes: “Motor disability, or Circuit Breaker stopped you from going out / Intellectual disability, or social distancing kept you from socialising / An eating disorder, or your favourite dining place has closed its doors / Declare your disability before the job interview, or you lose your job because simply there is no market for you.” In Stay Home Notice, a returnee from London (Tan Shou Chen) gazes out at his slick, alien island home from the glass windows of a five-star hotel – bringing together the loneliness of a hotel quarantine with the alienating experience of growing up queer in Singapore. I wondered if the Coronalogues were trying to mend this isolation by building interaction into the recorded experience. The pieces I relished the most were the ones that understood and made use of the strange borders of the mediated platforms we have come to rely on: whether it’s home-based learning for the thousands of students in Singapore (Miss Aruna Nair Teaches Plato’s Cave via Home-Based Learning in the Pandemic of 2020 by Michelle Tan), or how counsellors and therapists have had to adjust to conducting sessions online, set against the sharp increase in recorded domestic violence produced by confining survivors in unsafe spaces with perpetrators (I’m Fine, Really by Dora Tan).

Image: Nabilah and Corrie’s shared emotional responses and worries about a vulnerable protagonist during a major plot reveal for “I’m Fine, Really” written by Dora Tan and performed by Serene Chen.

Both works featured wonderful performances by Sindhura Kalidas (Miss Aruna Nair Teaches…) and Serene Chen (I’m Fine, Really; her sensitivity and understated presence broke my heart). As an educator and facilitator myself, I immediately recognised the cadences and coaxings that Miss Aruna Nair makes use of to bring her distracted students into the profound heart of the work she’s trying to teach. We enter a strange meta-reflective space where reality and fiction meet, where Miss Aruna discusses the machine she inhabits while pointing out the heightened simulacra and spectacle of pandemic realities. This is her world, but we are trapped in it too. As Miss Aruna raised her hand to the screen, I found myself raising my fleshy hand to meet her ghostly one, and then waving goodbye to someone who wasn’t there but is always there at the same time, fixed on a Facebook page for us to return and say goodbye to, again and again.

27 May, Wednesday, around dinner time / 4 June, Thursday, late afternoon (Corrie)

I’ve been thinking about audiences’ processes of recognising our own presences in a theatre. We might be standing in a theatre lobby or in the queue for the restroom. I see you, we exchange glances, grin, wave, acknowledge a having-been-there. We go through the rituals of entry – the beep of a scanner or the soft tear of a ticket stub, stumbling over the knees and feet of others in order to get to our seats – but also the rituals of departure. The lingering pools of chance encounters, or the hasty exit for the long train ride home where you’ll get to dissect every scene and flubbed line.

It’s so difficult to establish something as “an event” now, because the physical act of opening and closing a laptop, or swiping a finger across a smartphone screen, are the kinds of repetitive, forgettable gestures that don’t quite anchor us to the “eventfulness” of a thing taking place. I was reminded of the distentions of time that seem to be taking place – where time feels oddly compressed or strangely expanded. An event can feel like it is always happening. An event that took place in April can feel like it took place in January. The author Claudia Hammond, in this article for the BBC, suggests that “This blurring of identical days leads us to create fewer new memories, which is crucial to our sense of time perception. Memories are one of the ways that we judge how much time has passed.” She also talks about flashbulb memories – the kinds of indelible memories we make collectively during a major event, such as 9/11, or the death of LKY, or the worldwide protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death – where you can remember in great detail where you were or how you felt when you heard the news. During the long stretches of lockdown and home confinement, it’s hard to anchor ourselves to significant new memories if they aren’t flashbulb events.

Time is also folding over itself in this piece of writing. We’ve written these little letters to each other, this scrapbook of journal entries, mostly the week before – and here we are expanding and editing them, responding to each other, crossing between sentences. I’m wondering about the kinds of flashbulb memories performance can create. Which are the plays that have seared themselves into our consciousness? I remember the first time I watched Wild Rice’s Hotel in 2015, because there was a row of teenage boys in front of me who must have been 14 or 15. They entered the Victoria Theatre with a kind of rowdy bravado, all giggly and snarky. But at one point during the second act, during a particularly emotional scene, I realised that they were all quietly sobbing, completely gripped by the work.

4 June, Friday, 4.52pm (Nabilah)

I’ve been thinking about new dramaturgies, primarily of how to orientate audiences into this new world of theatre. It’s related to what you said about events – the rituals we go through while waiting for the room to darken, conditioned behaviours which prepare us for a show. These are the liminal spaces in which the mind can go into a soft reset, and I would argue that without these, a lot of online theatre ends up being impenetrable. It becomes harder to meet the performer where they are, even if the performances themselves are sincere. I think there are ways to mitigate this – such as having more transition time between plays. In the first session of Baca Skrip, Teater Ekamatra’s monthly series of live play readings on Zoom, playwright Irfan Kasban gave short introductions to his work before each of them were read. These were useful because not only do they give context to the work, they helped ease the audience into the world of the play. Long Distance Affair, an international production presented by Juggerknot Theatre Company and PopUP Theatrics, utilised Zoom breakout rooms as spaces for intimate monologues. Henrik Cheng and Michelle M. Lavergne acted as “navigators” for the audience in the waiting room, briefing us about what we might need to do inside a room or prepare beforehand (have a piece of paper or make sure you have enough space to move, for example). These “safety instructions” also help shape the expected etiquette of the audience members while watching the show.

In trying to forge a new kind of connection, the theatremaker or company must now consider how they can help channel their audiences’ attention, removing uncertainties and alleviating their anxieties – not an easy feat when the industry is under threat itself. Could these gestures of care make it into the permanent vocabularies of performance making, post-pandemic? The possibility of this, in a world torn apart by divisiveness, gives me hope.

Image: Sabrina Sng boxes in a box, in the Singapore monologue in Long Distance Affair.

May 28, Thursday, lunch / June 4, Thursday, late at night when it was raining (Corrie)

I’ve also been thinking a lot about the role of the critic and what it means to “respond” to performance. In the earlier weeks of the pandemic (and now, still), I’ve been going through a crisis of function both as a researcher and a writer. Even as I write this I am struggling with the meaninglessness of writing uncoupled from doing. Is writing doing? I used to be quite certain about this, but I’m not so sure any more. I return, again and again, to this piece on the possibilities of feminist ethnography written by anthopologist Elizabeth Enslin. Her Nepali niece, women’s rights activist Pramila Parajuli, tore into her when Enslin attempted to justify her writing and research as practice: “I want to say that you came to Nepal for two years, you wrote a book about the women’s movement, you did a Ph.D. But your work seems like nothing. Your book has no importance. After all, what is writing? You looked, you saw, you wrote a book. But that book won’t do anything if not accompanied by work, by practice. Right?” I also keep returning to Ghassan Hage’s recent terrific article reflecting on the “uselessness” of the academic and public intellectual (and by my own extension, the critic) in a crisis such as this one:

a critical intellectual, a professional whose job is to observe, think, reflect and convey ideas, can be a serious nuisance in circumstances of practical urgency. This is because the temporality of critique and the temporality of urgent practices are generally incompatible. Imagine someone instructing the captain of the Titanic, as he is trying to save whatever passengers he can, that they need to understand that colonialism was a factor in the tragedy everyone is in. Better be an activist than an intellectual in such situations, alerting third-class passengers of possible class and racial biases in accessing lifeboats, for instance. (2020: 2)

It’s very hard to write about a pandemic when you are in one, but to me two strands have emerged in artmaking and performance practice. There are those who argue that productivity and labour as part of the capitalist machine must pause, and that perhaps now is the time to not produce. To sit with sadness, or mourn what we have lost – that this non-producing is an act of rebellion we can finally embrace. Yes, we live in a brutal capitalist system that many people are working to dismantle. Yes, this all feels very mindful, very Buddhist, very “self-care”. But I am wary of the overlaps between non-producing and inaction, how quickly and easily one may slip into the other. I’m thinking about how white and non-Black supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement recently flooded Instagram with black squares for “Blackout Tuesday” (June 2) in an attempt at muting their own dominant voices. Frustrated activists and advocacy groups ended up straining to counter a deluge of performative activism that drowned out black and brown voices, as well as crucial information about the movement. Maybe the question is: what does it mean not to produce, but to act? I dare anyone with half a heart to prevent yourself from acting right now: anyone who has pledged themselves to antiracist work, or coordinated mutual aid listings, or worked with and donated to non-profit organisations. We must act, we must do. There are too many urgencies that we cannot ignore. In Manila, the fierce and phenomenal critic Katrina Stuart Santiago has set up a non-governmental organisation, PAGASA, that distributes food to families who need it, while keeping up her consistent and powerful critique of the state’s failures to protect and support its people (right now: the disturbing and deeply problematic new “anti-terrorism bill”). In Yogyakarta, dance dramaturg and critic Nia Agustina has been fundraising for emerging choreographers and helping artists to build home businesses that will tide them through a lockdown. In Singapore, book reviewers on Instagram have helped to establish a virtual book fair where 100% of the proceeds go towards mutual aid (as of this week, we’ve raised and disbursed more than $16,000). The critic also finds its shape in newsletters like Race Tuition Centre, a fantastic resource for Singaporeans interrogating the thin facade of Singapore’s “multicultural” identity, and the systemic, institutional and personal racisms that have taken root here.

A few weeks ago, I found myself utterly disenchanted with writing as I used to recognise it. I had enough of the gazillion hot takes on social media, how reactionary many of them were, everyone with an opinion to dispense and a bone to pick. What Ghassan Hage said: “Practical urgency and intellectual reflexivity are not exactly compatible.” Our discourse has become compacted and flattened into the extremes of social media: either you’re a flag-waving, Home-singing patriot or you’re a troll who’s out to destabilise the nation; either this performance is the best production you’ve ever watched or the worst thing ever to be uploaded on the internet. I can’t bear it. Instead I have been involved in mutual aid, food distribution, and putting together resource packs. I recognise the irony of writing even as I cannot bear to write.

Many practitioners in Singapore are taking this time to act on processes and systems that have, for a long time, been unhealthy for our ecology, and that we are now forced to reckon with: how pervasive and unchecked racism and xenophobia are in this country, invisible and asymmetrical labours of childcare and domestic work and how this coexists with artmaking, the precarity of technical and production crew, poor practices when it comes to contracts and payments, the different burdens that freelancers/independent artists and companies on grants face, and the monetary value we place on the art that is produced. And in that vein I appreciated the Coronalogues as a platform the Singapore Repertory Theatre commissioned to create as much work for freelance practitioners as possible.

28 May, Thursday, early dawn, confession hour (Nabilah)

I’ve already forgotten about Coronologues. Is that bad? I was very busy today and the bigger question for me was how to be a good advocate for the arts. Like: If I don’t catch this show online, is it bad? Lately I’ve been thinking if I should remove the word “critic” from my bio because I feel super unequipped for the new responsibilities that I feel it comes with now. I have nothing productive to say. What unique thing can I say with my voice? I rather stay quiet.

I think the other side of action is not just inaction, it’s also guilt.

27 May, Wednesday, 12.27pm (Corrie)

The night we watched the Coronalogues – or was it the night before? I actually can’t remember, because something about both evenings felt the same – I was so exhausted from work I lay down on the floor of my house in the middle of our tiny living/dining room and stared up at the fluorescent ring of light on the ceiling until my husband emerged from the study and asked me why I was lying on the floor. I could feel the words welling up inside me but nothing came out of my mouth. I lay there and looked at the ring of light and I started to cry, and he sat next to me for the next 30-40 minutes until I could sit back up again.

“It’s too big,” I told him. “It’s all too big.”

28 May, Thursday, 11.39pm (Corrie)

I attended five online events today, and I can’t feel my brain or my body any more. In the past, you wouldn’t think of attending more than three shows a week – even two shows was quite the feat. But now, in front of my laptop, I feel a greater anxious compulsion to attend as many things as possible – particularly because conferences and shows in faraway places that we normally would never be able to attend are now destinations we can teleport to.

1 June, Monday, 7.33pm (Nabilah)

I went for Baca Skrip. They did it Webinar-style, so we couldn’t see anyone else in the room except the performers. But people were chatting and there was a palpable feeling of excitement. In between the reads, I made jokes in the chat that apparently came out as “troll-like”. Processing it now, I think I was trying to calibrate my emotions. I was actually feeling overwhelmed, on the brink of crying even, because I have a close affinity to Irfan and his work. I think I was trying to leaven some of the heaviness.

Before I made any jokes, I had quickly texted Shaza Ishak, the company director of Teater Ekamatra, to check if it would be appropriate. I asked: “Is it a safe space?” “Yes,” she replied.

Image: Nabilah takes a screenshot of two Irfans in Baca Skrip: #HantaranBuatMangsaLupa

1 June, Monday, after dinner / 4 June, Friday, panic mode (Nabilah)

What I am taking away from these collective viewing experiences is the sense that we need to be kinder (to ourselves and) to the artmaking in these times. I love how technology is being used to experiment with the limits of storytelling, and the possibilities and impossibilities of theatre. There’s a deliciousness of the trial and error where I am relishing more in the trial and less with the error – in essence, supporting a kind of playfulness that happens to be taking place during a crisis.

For the audience, that tension is amplified when there is a sense of a loss of safety. In an actual theatre I know who is around me, and I know if I need to wait for the post-show to ask a question, or, if there’s something more difficult or nebulous to contend with, to grab a drink with my friends after. I know what I need to keep myself safe, in multiple senses of the word.

Image: Sindhura Kalidas confirms our worst fears in “Miss Aruna Nair Teaches Plato’s Cave via Home-Based Learning in the Pandemic of 2020” by Michelle Tan. “Very realistic,” says a commenter.

Facebook Live is a platform that throws the space wide open, making it feel less safe. Going back to Coronalogues, something like Miss Aruna Nair Teaches… acts against this, closing the frame so I know where I stand. I am a student in Miss Aruna’s class. You are a student in Miss Aruna’s class. In that moment, we are positioned as equals. The system may give her authority, but the pandemic has whittled that down somewhat – and we see it in the way she has to manoeuvre around the limits of technology, how she tries to make eye contact but doesn’t always manage to, in the inviting language she uses – all these gestures creating the feeling of shared space that we associate with theatre. In You’ve Been Here… All Along, Wheelsmith flips the switch on this, reminding us of our privilege before the pandemic, relative to people with disabilities. For the audience, it’s confronting and yet not confrontational, as he makes great use of the confessional tone of spoken word poetry, heightened by the literal calls to prayer (an unseen person addresses him and he retracts from the camera to perform his obligation) which break up the lines. Jo Tan’s Stay Home Notice posits a gay Singaporean man under quarantine in a fancy hotel as a kind of Shroedinger’s cat, both welcomed and not welcomed in the country. The term “biological terrorist” (to quote the playwright), when viewed against the lens of the stigmatisation of HIV/AIDS patients, becomes a metaphor of infection that hits close to the bone.

For some, the theatre used to be that safe space where we could discover stories like these. Perhaps what we lack in safety now, we try to make up for in the act of solidarity – watching, commenting, liking, care reacting. Where it would be life-threatening in public spaces, there is safety in numbers online.

31 May, Sunday, 2.41am / 31 May, 9.32pm / 5 June, Friday, hungry (Corrie)

I participated in one of the last few sessions of A Long Distance Affair over Zoom. Throughout the piece, which dematerialises and rematerialises the spectator into tiny Zoom breakout rooms across the globe (from Singapore to Paris and Miami), you’re constantly in frame, looking at yourself performing spectatorship. My fellow “travellers” were generous and enthusiastic, and I found myself moved by their openness to play with the medium and engage with the performers on screen.

The performance scholar Keren Zaiontz has examined “narcissistic spectatorship” in immersive performance, where she writes about Audience (2011) by the Belgian performance company Ontroerend Goed. It’s a participatory piece where “a live feed the size of the stage that reflected the image of the audience back to themselves as a seated mass. The audience was, in effect, the set, the locus of the action” (Zaiontz 2014: 406). That was six years ago, and this paragraph – once spelling out the uniqueness of Ontroerend Goed’s confronting work – could now literally be used to describe most “live” performances on Zoom or other video conferencing platforms. Zaiontz doesn’t use “narcissism” in the psychoanalytic sense. After all, she argues: “no mode of theatre or performance reception can be completely selfless. As long as performance is an act of transmission that commands spectators to read, feel, analyze, and identify with what they witness onstage through their own bodies, then spectatorship will remain a self-centered interpretive act” (2014: 407).

Whether we call ourselves critic or spectator, we witness performance through the medium and conduit of our selves. We respond to work, and deem it “bad” or “good”, according to the various cultural and educational capitals we have access to – which are in term informed by structures of power, including race, class and gender. Your standards of taste are never neutral. Your response to a work reveals the kind of schools you were privileged (or not privileged) enough to attend, the disposable income you buy theatre tickets with, the racial biases you have been steeping in since you were a child. What are we spectating and watching now? What passes through the porousness of our bodies? How can the “self-centered interpretive act” be used for good? I strongly feel that the demands of the critic have shifted beyond responding to and picking at the aesthetics of performance – to also acting with and for the community within which they are embedded.

2 June, Tuesday, 12.35am / 5 June, Friday, on an empty stomach (Nabilah)

I definitely think the Critic with a capital C is unimportant now.

This reminds me of a board game I created last year, which combines an art reviewer’s journey with Monopoly-like game mechanics. Created for students, the objective of the game was to make it all the way around the board, while dealing with scenarios which tested the ethics and values of the player. I named the game The _____ Reviewer, because I wanted the students to reflect about their positionality as critics. The critic doesn’t write in a vacuum, their work depends very much on their background, value systems, privilege or lack thereof, who their readers are, the politics of the platform they write for, the artists whose work they are critiquing. The game is fairly simple in design, but even without the financial transactions of Monopoly, it takes hours to complete because the player has to defend and justify their actions, and convince the public (i.e. other players) that an action they are taking is “right”. Looking back now, I am a little uncomfortable with not only the centrality of the critic in the game, but the nature of the gameplay itself. Anyone could “win”, as long as they could successfully define and defend their own narratives of their world.

The critic champions, the critic doesn’t play for individual wins. What is happening around us now, the fight for the rights of oppressed minorities in mass movements like Black Lives Matter and its ripple effects across the world, the indefatigable work of activists in Singapore in fighting for the rights of our migrant communities and questioning how the system fails minority groups, what is happening in the Philippines with protests against a newly proposed anti-terror bill, shows how important the critical voice is. The work of critics is necessarily plugged into the concerns of their communities. When the work is difficult, it is even more important to continue writing, speaking, communicating.

On the one hand, this piece may be read as mere lamentations by a pair of tortured critics. Part of that is true, but there is something to be said about trying to work through ideas of what it means to produce, receive or consume art, in the context of a pandemic, of climate change, of an awakening of civic consciousness – even if it means getting stuck in the process of unknotting our still-forming ideas, and exposing the soft bellies of our more emotional impulses. Some structures are meant to be interrogated, re-considered, re-imagined and dismantled – in its own small way perhaps what this is, is action in progress.

Image: Thank you for reading us. Love, Corrie & Nabilah.

Additional references and further reading

Directors Lab West (2020) “Using Intimacy Direction to Create a Culture of Consent Post-COVID” held on Facebook Live and presented by Directors Lab West on 25 May 2020. https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=855880401562608&ref=watch_permalink

Elizabeth Enslin (1994) “Beyond Writing: Feminist Practice and the Limitations of Ethnography”, Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 537-568.

Ghassan Hage (2020) “The haunting figure of the useless academic: Critical thinking in coronavirus time”, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 0(0), pp. 1–5.

Kambole Campbell (2020) “Black Squares Don’t Save Black Lives”, Hyperallergic, June 4. https://hyperallergic.com/568933/black-lives-matter-white-allies-social-media/

Katrina Stuart Santiago (2020) “From dream to dystopia: The cultural critic in the age of pandemic”, Arts Equator, May 21. https://artsequator.com/from-dream-to-dystopia-the-cultural-critic-in-the-age-of-pandemic/

Keren Zaiontz (2014) “Narcissistic Spectatorship in Immersive and One-on-One Performance”, Theatre Journal, Vol. 66 No. 3, pp. 405-425.

Pierre Bourdieu (1979/1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, translated from French to English by Richard Nice. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Race Tuition Centre (2019-present) https://tuition.substack.com

Shailey Hingorani (2020) “Isolated with your abuser? Why COVID-19 outbreak has seen uptick in family violence”, AWARE: Association of Women for Action and Research, March 26. https://www.aware.org.sg/2020/03/isolated-with-your-abuser-why-covid-19-outbreak-has-seen-uptick-in-family-violence/

You can watch Singapore Repertory Theatre’s The Coronalogues: Silver Linings, as well as its rehearsed reading of Jean Tay’s Boom here. The next edition of Baca Skrip by Teater Ekamatra on 26 June, 8pm, will feature a reading of Anak Melayu by Noor Effendy Ibrahim.

Nabilah Said is the editor of ArtsEquator.

Corrie Tan is a practitioner-researcher from Singapore. She is currently a PhD candidate in Theatre Studies at the National University of Singapore and King’s College London, where she is researching performance criticism in Southeast Asia.

We would like to thank Kathy Rowland and Loo Zihan for their feedback on this work.