Art that Moves is an occasional series where we ask artists and other creative workers to reflect on artworks, performances or events that were personally important to them.

Han Xuemei, Dramabox‘s Resident Artist, is one of the main facilitators for Dramabox’s re-run of the The Lesson (5 – 22 July 2017), a critically-praised work that places the audience and their choices about their lived environment front and centre.

This week, Han Xuemei shares with us her musings on It Won’t Be Too Long (2015) by the company. The production dealt with the issues surrounding the exhumation of graves at Bukit Brown cemetery to accommodate the expansion of a highway.

ArtsEquator (AE): Good morning Xuemei!

Han Xuemei (HX): Morning.

AE: Thanks coming on for the Art That Moves series. So, you’re a young maker. Can you tell us about a work of art that has moved you?

HX: I will talk about a recent work that moved me – It Won’t Be Too Long (2015) by Drama Box (Heng Leun and other collaborators Li Xie and Wan Ching). The production was about the issues surrounding the exhumation of graves at Bukit Brown cemetery to accommodate the expansion of a highway.

It comprised of 3 distinct parts: The Cemetery (Dawn), The Cemetery (Dusk) and The Lesson.

The Cemetery (Dawn) was a site-specific movement piece at Bukit Brown, and we had to go to the cemetery at about 5:45 a.m. to watch the performance.

The Cemetery (Dusk) was a verbatim theatre performance at SOTA’s black box, and involved various interviews with stakeholders of the Bukit Brown issue.

Finally, The Lesson is a participatory experience, where as audience, we had to partake in the decision-making process of a land contestation issue.

AE: Was Jean Tay also involved as a writer?

HX: Yes, she was involved in Dusk, organising the interviews that the team has gotten, and coming up with a dramaturgy for the piece.

As for why this work left such an impression on me, firstly, it has to do with my personal interest in the issue of land contestation in Singapore, which isn’t something that I’ve always known about. I only started to look at the issue when I started my journey as a theatre practitioner, and I had done adaptations of Kuo Pao Kun’s Silly Little Girl and Funny Old Tree (2014), as well as Kopitiam (2016).

My involvement in Drama Box’s IgnorLAND series also got me interested in the issue surrounding land/public space ownership and the politics involved.

So it was at a point in my life when I was asking myself questions like: Who owns public/community space? If public/community space is meant to serve the needs of the public/community, who should be included in the dialogue about how these spaces are being utilised?

How much power does the government have, and how much power should the public/community have? How can the planning and decision-making process look after the conflicting needs of different groups of people? And so on.

AE: These are issues that Dramabox has been involved in for some time, and you’ve been with the company since 2012. What stood out about this work in particular? Was it the form – three interrelated works, the audience agency? The themes?

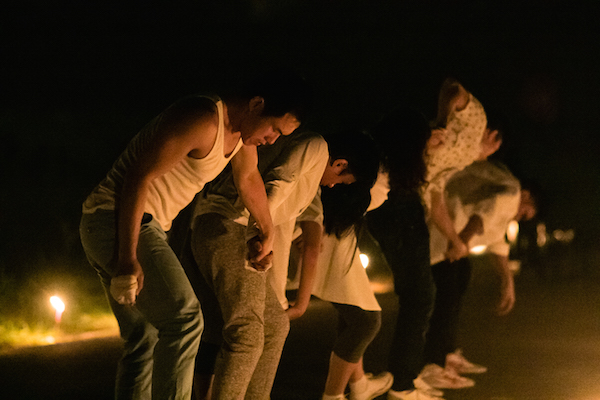

HX: I thought this work was very ambitious in terms of the three interrelated pieces and the different aspects that they addressed. For me, Dawn spoke to me in a visceral way – there is no spoken dialogue, it was just movement for about 1 hour, and somehow, as I was watching it, I felt like I was watching the spirits of Bukit Brown, and in that moment, I felt something (not in the sixth sense kind of way) about the place, that it was a place of comfort.

And that feeling also reminded me that it’s difficult to quantify or put in words to explain a feeling that you experience when you are in a place. You have to experience it for yourself, and the place has to be around for that experience to occur.

There was one moment in the piece: We were watching the piece in darkness – you could make out the silhouettes of the actors – and they were pushing something bulky up on a slope, something that looked like a coffin of sorts.

Then at the end of the piece, because the day has broken, you suddenly see that that bulky item was actually a piano, and one of the actors started playing classical music. So it was like classical music in a cemetery and all around us, we saw the tombstones, and somewhere further down the road, you also see the construction hoardings, and I was just asking myself “What are we doing to this place?”

Then for Dusk, it was an entirely different kind of experience, a lot of text, a lot of different opinions from different stakeholders, and in a way, it was more an intellectual challenge, making us think about the issue in an intellectual way.

The familiar argument was that we cannot please everyone, that Singapore is land-scarce, but in one of the interviews, the interviewee was actually challenging the notion of scarcity. I still remember the question that he asked: “How can Singapore be land-scarce when we have xx number of golf courses?” And we are watching 3 actors playing multiple stakeholders making different arguments for and against, while the movement actors that we saw earlier in the day were doing their movement on stage as well.

So it was kind of like “where is that story in our debate about whether or not to keep the graves intact?” Do the concerns of the living matter more than the dead? Is that how decisions should be made?

AE: The Bukit Brown issue has been an emotional one, that has galvanised different communities/sectors of the public/activist/government. How do you think art – and in this case, It Won’t Be too Long – gave you an insight into something beyond the arguments “for and against”?

HX: In response to your question, I would say the entire experience culminated in The Lesson, and that helped push me beyond looking at the arguments of for and against. I feel the interrelatedness matters a lot in this work. So in the first 2 parts about The Cemetery, as an audience, I was watching the issue as an observer, as an “outsider”.

But this position is challenged in The Lesson, where I now have to partake in this decision-making. The scenario in The Lesson is that in order to make way for a new MRT station, we are given 7 sites to choose from, out of which 1 of them has to be demolished.

So the first challenge is a personal one: How do I choose? What do I consider when making my choices?

Then I have to present and argue for my choice to the other members of the community: How do I listen to their choices and priorities? And when our values and priorities differ, how do we negotiate that?

I think the creative team also set a very interesting rule that if we are unable to agree amongst ourselves, then the decision will be made by the government. That brings about another consideration: Do we want to keep the “power” or do we relinquish it because we cannot agree as a community?

But then, someone in the audience also asked the question: “Why do we have to have the MRT station? Who decided the 7 sites? Why can’t we choose something outside of these 7 sites?” — which is why I put inverted commas for the word power in my earlier sentence. Because this entire participatory dialogue/ experience got me to question the concept of power in land contestation issues.

We are so engrossed in talking about why we should keep/remove Bukit Brown (or any other contested sites) that we forget to question why, in the first place, do we have to make this decision? Why do we need to have this discussion?

Maybe it doesn’t have to be so binary… maybe we can still make things work if we see it beyond black and white.

And sometimes, the way we do consultation here can be misunderstood as a way of giving power to the people, but is that real power?

AE: Could you share with our readers how this experience – of making this work, and participating in it within different positions of “power” has impacted the way you as an artist are moving forward?

HX: For me, it is interesting to challenge ways in which we are used to “consuming” artworks/ performances, like how It Won’t Be Too Long did in some ways – the timing of the performance (dawn!), the scale of it in terms of having three parts.

I would like to investigate this power relations in my future works in terms of the artist-audience relationship: What happens when the artist gives the audience more or less power?

Also, the idea of how much does an audience invest in a production (besides paying for it) by participating in the work itself.

The Lesson, featuring Go Li, the moving theatre will be on at the venues below. For more information, go here.

Venue & Date

5 – 8 July 2017

@ Open space beside Tan Quee Lan Street (Bugis)

12 – 15 July 2017

@ Open Space before Blk 127 Toa Payoh Lor 1 (Market)

19 – 22 July 2017

@ Open Space outside Hougang MRT Exit B (beside Hougang Mall)

Han Xuemei is an artist who takes an interdisciplinary approach towards theatre-making. Her methodology stems from her belief in the ephemeral and ever-evolving nature of art and life, which provides the potential for interventions and change. She embraces the possibilities that are generated by chance and unpredictability, and this fuels her exploration of the participatory processes that expands the role of the spectator.

Since joining Drama Box as a resident artist in 2012, Xuemei has co-created a few of the company’s socially-engaged projects, such as IgnorLAND of its Time (2014), SCENES: Forum Theatre (2015) and IgnorLAND of its Loss (2016). She has also directed and facilitated some of the company’s theatre for young people, including forum theatre plays 40 Strokes (2013), sixpointnine (2015), as well as adaptations of Kuo Pao Kun’s plays – Silly Little Girl, Funny Old Tree (2014) and Kopitiam (2016).