Singapore’s bicentennial year in 2019 sparked great discussion and debate about the legacies of imperialism and colonialism, which continues till today, in step with larger conversations happening globally around decolonisation, indigeneity and civil rights.

With the third edition of The Arts House’ LumiNation festival focusing on migration, historian and academic Timothy P. Barnard delves into an area not many have explored – the impact of imperialism on animals and the environment in Singapore.

His talk, Imperial Creatures, which takes place online on 16 August, 4pm, will look at how power structures since the colonial era have impacted both human and animal communities, the effects on our ecology and even how we relate to one another today. The talk draws from his latest book, Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819–1942, which was recently nominated for best non-fiction title by the Singapore Book Awards 2020.

ArtsEquator speaks to Timothy, currently Associate Professor in the Department of History at National University of Singapore, about his interest in this area and why people should learn about the history of animal movement and presence in Singapore since 1819.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed.

ArtsEquator: How did you get started in this area of research?

Timothy: When I was originally hired 21 years ago to teach in NUS, I came and I taught courses on Southeast Asian history. I developed a course where I took Honours students through the archives and we discovered what was available to us as a resource for understanding the Singaporean past. I began to realise the wealth of material that’s available in our archives, our libraries, and other areas. Combined with my own interests in the environment, with local history and Southeast Asian history, it all came together in studying about Singapore, but through an environmental angle.

ArtsEquator: What was the first thing that you uncovered that made you feel like–

Timothy: The ‘lightning bolt’ moment? One of them was I put together an edited collection, published under the title Nature Contained, which comprises different accounts of the Singaporean environment in the last 200 years. In that book, there is a chapter by Nigel Taylor who used to be the director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, and we came to develop an Honours module together that took place in the Gardens. I realised, wow, there’s this whole history of this imperial institution that we now think of as a park in Singapore. That led to me writing a book about the Singapore Botanic Gardens, called Nature’s Colony.

The Botanic Gardens was where the first public zoo existed in Singapore, between 1875 and 1905. Writing about that zoo introduced me to ideas about animals in Singapore. That led to this book about the role of animals in imperial history, where I also talk about massive deforestation and how it changed the environment of Singapore. The environmental crisis that Singapore experienced in the 19th century is a theme that runs through all of my books because it influenced a lot of the colonial government’s response to how they were going to live or be present in Singapore. And that’s often not understood. Many other works on Singaporean history focus simply on politics or great men.

ArtsEquator: Why do you think people focus mainly on great men?

Timothy: Traditional approaches to history are often wrapped up in politics and military issues. There is what is often called ‘great men’ history, the idea that everything is dependent on one iconic figure who determines all. Raffles would be a good example of such a figure in Singaporean history. This is a guy who was in Singapore for a very limited amount of time. Often his policies, or whatever vision he may have had, were not followed. He was a problematic figure in his own right. However, he’s become this great icon of Singaporean history.

If we simply depend upon ‘great men’ history, it leaves a lot of gaps in how we understand our past. Dealing with the environment helps us better, no pun intended, root ourselves in our past or place ourselves in perspectives that seem more relevant to our own experiences here. Rather than, ‘oh, some great man was making a decision and that is the end of the story’. We need to think about the effects of things, how we fit into this, our own role in this.

Horse Gharry, 1930s. Courtesy of NUS Press.

ArtsEquator: So we’re more connected to how the natural environment has evolved rather than the icons that are celebrated?

Timothy: Sure, some of these icons made decisions. You can say, Raffles collected natural history specimens. Or let’s take one of the other great men of Singapore in history, Lee Kuan Yew. He was a champion of the gardening programmes that have made Singapore a green, garden city. I think that’s a wonderful thing – I like living in a garden city. But we need to look beyond ‘okay, the great man made a decision’. We need to think: What did that mean? How did it transform the environment? How did it affect our lives? It’s not simply about a decision that was made.

ArtsEquator: Can you share what your talk Imperial Creatures will be about?

Timothy: When we think of immigration in Singapore, we usually equate it with people in labour groups in the 19th and 20th centuries – coolies, people working in the docks, agriculturalists, farmers. And of course it’s a sensitive political topic today, when people are talking about immigration related to employment, and integration into society. But what we have to also realise is that, in many respects, almost every creature – by that I mean animal, human, whatever we want – in Singapore today is an immigrant. In the sense that when the British East India Company arrived in 1819, they completely transformed the environment.

I know we live in a tropical environment, but it was shaped completely by this imperial force. They deforested the land and then planted what they wanted. They brought in their own crops, whether it be rubber, or pepper, or nutmeg – things that were not native to Singapore. And they brought in, not just people, also plants and animals that have transformed the environment and our societies. Horses, bullock carts that were used to transport goods and people, dogs, all types of pets. You could almost say tigers were migrants to Singapore, because by deforesting the land, you create an environment in which tigers could thrive.

ArtsEquator: Before that, we didn’t have dogs?

Timothy: There were dogs – apparently all communities in Southeast Asia had dogs – but the difference is, when the British brought in dogs, they were high-bred pets. They were terriers, poodles, dachshunds. These were actual imperial creatures, these were dogs that represented your status. So the idea of owning a pet is an imported idea. That then transforms our relationship to animals on the island, but also our relationship to each other.

The stories of these animals are really metaphors for our own human experience. When animals come in, they are monitored. They are controlled. Rules and regulations develop around them. They are allowed in or chosen for particular purposes. Just as our ancestors were brought in to be workers, various types of roles. Through their stories, we can learn more about our own human imperial past or the role of imperialism.

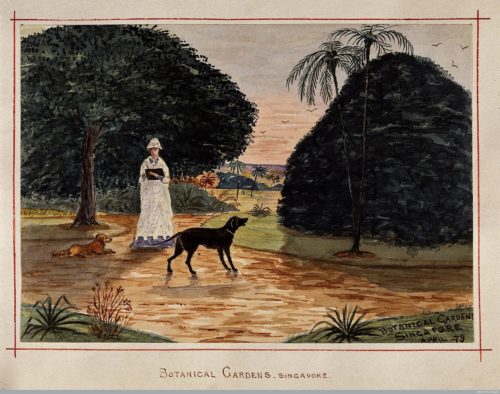

Illustration of European Visiting the Singapore Botanic Gardens with Dogs. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Courtesy of NUS Press.

ArtsEquator: How does environmental imperialism fit into the larger movement of countries trying to decolonise?

Timothy: What we need to realise is how much of this is a legacy. We live in a society today, through whatever process of decolonisation may have taken place, which still follows legal precepts brought in from England. There are a variety of legacies of imperialism. Animals are simply one aspect of that. And so when people cherish their pets as members of the family and things like that, you can say that it’s an imperial legacy. We need to discuss issues of imperialism here. And if we can do it through the metaphor of animals, that might make it easier to ease us into the topic a bit. But it is something I think needs to be done.

ArtsEquator: Do you feel like the topic of the history of animals here, or even metaphors related to them, have been sidelined?

Timothy: I don’t think it’s been sidelined – it’s never been picked up. (laughs) You could say it’s sidelined from earlier historiographical approaches. In Malay historiography, in Malay hikayats (epics) and syairs (poetry), animals play a very important role. They act as metaphors, as symbols of larger issues and other things. For example, I begin the book with Singapura Di Langgar Todak, the story about swordfish attacking Singapore. But swordfish didn’t attack Singapore. It’s a fable to tell a larger story. I guess you could say in the book, and in a lot of what I’m doing right now, I’m reviving a modernised version of that. Not necessarily telling fables, but using animals to help us better understand a specific perspective or aspect of our past.

ArtsEquator: That’s fascinating.

Timothy: When I was a historian of the Malay world, I read plenty of hikayats and syairs. I was used to the flowery Malay language, animals and other things, when I was dealing with sources of the past here – a very rich, wonderful combination of history and literature. And then, boom! It’s like, 1819, it’s got to be written in a boring political fashion. Even the Hikayat Abdullah – held up as a great Malay text of the 19th century – doesn’t have that literary flair of earlier hikayats. Once you hit 1819 onwards, they become more Europeanised, more westernised. We’ve lost a bit of that storytelling ability to convey information about the past, through following specific westernised approaches. Of course as a historian, I use these same approaches – footnotes, sources – but I think we need to hark back to this earlier storytelling approach. We learn the lessons a lot easier.

ArtsEquator: What are your hopes for this talk?

Timothy: For people to think about how we got to where we are today. It’s a very complex inner workings of people and environments and how it all came together. It’s not simply top-down – top-down does play an important role, they’re making policy decisions that ultimately influence us – but it’s also how people react, it’s how these different things intersect. And it’s not just bounded by Singapore. We’re influenced by outside issues that come in – the idea of importing animals from Britain, tigers swimming over from Malaysia, all these influenced our society and how we understand it.

This article is sponsored by The Arts House. LumiNation runs from 1 to 30 August, with various talks, presentations and programmes on the theme of migration and national identity. Read more here.

An earlier article on the Orang Phebien, or the Baweanese community in Singapore, was published on ArtsEquator. You can read it here.

ArtsEquator needs your support. Please visit our fundraising page to find out more about Project Ctrl+S ArtsEquator. ArtsEquator Ltd. is a Singapore-registered charity.

About the author(s)

Nabilah Said

Nabilah Said is an award-winning playwright, editor and cultural commentator. She is also an artist who works with text across various artforms and formats. Her plays have been staged in Singapore and London, including ANGKAT, which won Best Original Script at the 2020 Life Theatre Awards. Nabilah is the former editor of ArtsEquator.