Introduction

In 2022, ArtsEquator, in collaboration with Five Arts Center initiated the Southeast Asian Arts Censorship Database Project. The Pilot focused on six countries: Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, The Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, documenting cases over a 12-year period, between 2010 – 2022.

Objectives

Arts and cultural practices have a long history of being censored and suppressed across the region, under the different colonial administrations1, and by subsequent national governments. While many violations against artistic freedom make the news locally and abroad, there is a lack of proper documentation across the region. The lack of public records and fading institutional memory shields the perpetrators and enables a double silencing, beyond the material act imposed on the work or creator.

Further, the paucity of reliable data on arts censorship at a national and regional level impedes the efforts of artists and advocates to enact changes in legislation to protect the arts and cultural rights of artists and audiences.

The objective of the SEA Arts Censorship Database is to support cultural and artistic rights in the region by:

- creating a system of monitoring and documenting violations against artistic freedom across the region

- generating data-supported information to identify patterns and trends in the curtailment of artistic freedom in Southeast Asia

Scope of the Pilot

Researchers in six countries were involved in the pilot, which focused on incidents between 2010 – 2022 only.

Reaksmey Yean and Kai Brennert (Cambodia), Adrian Jonathan Pasaribu (Indonesia), Zikri Rahman (Malaysia), Katrina Staurt Santiago (The Philippines), Linh Le (Vietnam) and Sudarat Musikawong (Thailand), conducted desktop research to document violations against freedom of expression in the arts (FOEA). Sources included media reports, national archives, social media, arts publications and other sources. Researchers also conducted interviews with artists to document cases outside the public domain.

Forms

To gain a full picture of the threats to artistic freedom, we recorded data across 8 different forms and practices caught in the cross hairs of state surveillance or public-driven culture wars: Visual arts, Performing Arts, Publications/literary arts, Music, Broadcast/social media, Film, Culture and Customs, and Multidisciplinary practices.

Violations

To capture the fluctuating temperature of artistic freedom, we widen our scope beyond clearly identifiable acts of repression such as cuts, bans or legal actions. We also included challenges, public performances of outrage, gatekeeping by stakeholders and the like. Such challenges and speech acts may not ultimately lead to proscription. Yet, the process of being questioned, challenged or criticised in and of itself is a form of incrementalised repression that can have long-term effects on the arts community and the public in general.

Baseline information

The research attempts to break down the what, who, why, how and the “what happened next” when a violation happens. The priority was to capture baseline information about incidents rather than to create detailed case studies. The aim was to generate quantitative data on the number of threats, the frequency of methods used, and the agents of censorship, to name only the most obvious.

Working on the ground

In practice, violations of artistic freedom are seldom precise or easily reduced to clean data points. As artists well know, the lived experience of censorship and repression of the arts is messy, slippery and unpredictable.

Within a single case, there may be multiple agents, each using unique methods to constrict the art work, silence the creator and punish the presenter.

The justifications for constricting artistic free expression are sometimes bewildering. Artists are accused of transgressing boundaries that seem amorphous. Often, the official reason for challenging a work or event is a smoke screen to hide more nakedly political agendas.

Many proscriptions and challenges are based on meanings and values inferred or imposed upon the artwork by different parties. There are times this is done cynically, to spark controversy and then earn brownie points as defenders of faith, culture, national identity, royalty, the country, women, children and the like.

For the creator or presenter, in that moment of challenge, extreme anxiety, uncertainty, fear or exhaustion might override their instinct to assert their rights to artistic freedom.

Responses from the arts community may begin with indifference, move towards allyship and then as the threat increases, or fatigue sets in, evaporate.

Consequently, our findings go beyond the sharp bones of a purely quantitative research project, as we try to capture and distil the interplay of push and pull, overt and subtle, compliance and defiance which makes up the reality on the ground.

The following report captures, in numbers and narratives, the key findings from this six-country2 documentation project. It covers general findings, with examples and analysis to give readers a broad overview. This report can be read in conjunction with the individual country reports produced by the country researchers, available here.

Several of the key findings will not be a surprise to anyone who has followed the arts sector in recent years. Indeed, the data justifies the sense of disquiet about the state of artistic freedom that has previously only been informed by anecdotal accounts.

What is targeted

Of the 652 cases documented, film, publications and visual art were the three forms most frequently targeted over the 12-year period under study.

Movies, books and magazines are amongst the most widely circulated cultural products. This potential to reach a large, general public is presumably one reason for greater control. Further, both these forms have entrenched legal and regulatory frameworks, some of which go back to colonial times.

The regulation of films and publications is efficient and widespread, and usually supported by law. Of the 141 publications proscribed, 105 violations were supported by law or a formal process. 176 films were targeted, of which 137 cases were carried out by agencies mandated to regulate such products. These two forms stand in contrast to other forms tracked, a higher proportion of which are challenged without clear legal basis.

Of the 176 films and documentaries targeted, 57% were made by Southeast Asians, ie. local filmmakers, such as 3.50 by Cambodian filmmaker Chhay Bora, about prostitution in Cambodia. 43% were foreign films, including several Hollywood feature films. The state was the principal agent of censorship, responsible for 150 bans, cuts or other restrictive methods.

Visual art, on the surface, appears to be more niche, without the wide circulation of film and publications. However, going deeper, we found that of the 102 visual art cases, the biggest slice, 33%, were murals, monuments, sculptures or graffiti, located in public spaces, rather than in a gallery. Accusations of damage to public property, defacement or vandalism were used to remove street art and graffiti, particularly those that raised social issues. In the Philippines, Panday Sining, the cultural arm of a youth activist organisation, posted graffiti as “a response to the worsening economic and political state of the nation” in a city underpass. The Mayor of Manila, threatened the group on FB, saying, “If I catch you, I will make you lick those walls clean”. Members of the group were arrested and held for nine days without formal charges before they were released. The attacks on public art supports the argument that cultural goods that have a wider circulation or public access are more likely to be proscribed or face challenges.

Online or broadcast media includes TV programs, video games, webs series, memes, advertisements etc. This was the 4th most frequently targeted sector, with 83 total cases. More than half of that number were TV series, on broadcast or streaming services. Advertisements were also attacked. In 2021, the makers of sanitary pads were forced to apologise after a religious group objected to the vulva-inspired flowers on the packaging. Social media content only accounted for 21% out of the 83 cases, which is likely due to the difficulty of policing online content. This sector will face increased surveillance in the future, as several countries in the region have already, or will be, introducing laws to regulate online content and streaming services.

Who violates – Primary Agent

The field is complex, with multiple stakeholders and agents that restrict FOEA. To understand who the greatest violators are, we asked two questions. First, we asked the researchers to identify the primary agent – the party which caused the most damage or used the most impactful method in each case. Second, we asked if there were secondary agents involved.

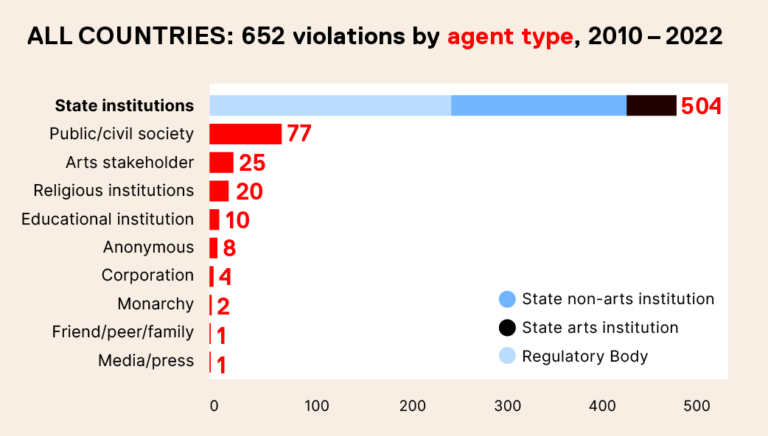

The answer to the first question was unequivocal. The state was the most active, and efficient agent, responsible for 77% of the 652 cases. This was followed by the public, a distant 12%, arts stakeholders at 4% and religious institutions, at a mere 3%.

The State

State institutions were responsible for 504 violations. The data broke down the state into smaller categories, providing more granular detail about the violations enacted by three different kinds of state agencies: regulators, state non-arts agencies and state arts agencies.

Regulators

Regulators are government bodies which have the legal mandate to control creation and distribution of arts and culture, such as The Bureau of Publishing, Printing and Issuing (Vietnam), Film Censorship Board (Malaysia) and the Covid Taskforce (Indonesia). Such state regulators were responsible for 257 violations.

State non-arts agencies

Next were state agencies which, ostensibly, do not have oversight to control arts and culture, yet violated artistic free speech through a variety of methods in 187 cases.

To cite two examples: In 2019, the Ministry of Education Malaysia investigated a school for ‘anti-palm oil propaganda activities’, after the Minister of Primary Industries accused the school’s student play of seeding hate towards one of the country’s biggest industries.

Bang-La-Merd, a solo performance by Ornanong Thaisriwong that explored the impact of Thailand’s lese majeste (Article 112) law, was first staged in 2012 without incident. However, a 2015 restaging required a permit from the Military National Security3. Further, a uniformed soldier attended and video recorded each performance creating fear and intimidation in the cast and audience.

State arts and cultural agencies

State arts and culture agencies, such as a public museum or the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, were a smaller player, but perhaps the more interesting. These institutions are tasked with developing and supporting the arts sector, within boundaries that buttressed the political elite’s narrative of national culture and identity. When artworks breach these borders, the very agencies which fund and develop the sector become disciplinary agents, responsible for 60 out of the 504 violations against artistic expression by the state.

The Public

As the primary agent, the public – individuals, netizens, formal or informal groups and the like – accounted for only 12% of the total number of cases, a far second to the State.

Indonesia and the Philippines had the most activated publics, but across all six countries, there were cases of civil society groups or netizens who coalesced around issues of religion, morality or culture and exerted enough pressure to censor works or shut down artistic events.

Women were particularly vulnerable, facing attacks curtailing their bodily autonomy and freedom to participate in cultural life. In Malaysia, a Facebook group, Thaipusam Spraying Group, with 140 members, threatened to spray paint on Hindu women dressed “inappropriately” during the Hindu festival of Thaipusam.

Professional associations, such as those for nurses, teachers and the police were also guilty of violations against artistic freedom, with members protesting or demanding bans of works that portrayed their profession in a less than flattering way.

Arts stakeholders

Arts stakeholders accounted for a small number, active as primary agents in 25 out of 652 cases documented. This group included stakeholders such as Bandung Book Fair (Indonesia), Galeri Petronas (Malaysia) and Writers Association Publishing House (Vietnam).

Often such organisations are compelled to exert pressure, remove work, or withdraw resources from artists they are collaborating with out of fear for their own safety or organisational longevity. An exhibition by Mass Art Project at the Jim Thompson Arts Centre (Thailand) in 2021, featured a life-size cardboard cutout of then-Thai Premier, General Prayut Chan-Ocha. The Art Center staff asked the artists to remove the image for fear of antagonising the military.

These 25 cases make up only about 4% of the total incidents in the database. However, the data collected has some flexibility in the way it is read. If we collapse the barrier between state and private arts stakeholders, the figures can be more concerning. Combining violations by state-owned arts agencies and general arts stakeholders raises the number of violations by arts stakeholders to 85. This elevates arts stakeholders to the 2nd most active agent of censorship, albeit still far behind the state.

Using this lens allows us to capture how, over the past decade or so, many countries in SEA have invested state and corporate resources into developing the creative industries as a new pillar of their economies. The influx of funds has grown state and private arts infrastructures and benefited artists and the public in many instances.

However, one can argue that an undesirable outcome is the outsourcing of surveillance and control of artistic expression into the hands of a range of organisations and individuals along the arts and culture ecosystem. Each layer of administrator, artistic director or venue operator could potentially become activated to violate artistic freedom, in order to protect themselves from punitive measures by those higher up the arts food chain.

The acts of suppression become dispersed, diffused, reproduced. It is not easily identified as repressive, especially when it is enacted by a peer and perhaps framed as a curatorial, artistic or financial decision. It may also go unreported as these often take place behind the scenes, before the work hits the public.

These kinds of violations, (if they are even conceived as such by artists themselves), are harder to challenge, given the professional and personal relationships that make up the arts ecosystem. This is an area that requires further research and scrutiny, to fully understand the potential impact posed by arts stakeholders on freedom of expression in the arts.

Who violates – Secondary agents

On the ground, artists often recount being attacked from many sides, and indeed, the data reveals that 219 cases had more than one agent involved in violating artistic freedom.

The most frequent secondary agents were from the state (98 cases) and the public (93 cases). This near parity between the State and public is in contrast to the dominance of the state as the primary violating agent, as we saw earlier. It proves that citizens are an increasingly potent threat to artistic freedom, often using their voices to push the state to exercise even more of its disciplinary power on arts and culture.

But the flow of action is not simply one way. Arguably, many of the governments in this study, (and the religious establishments which buttress them) have spent decades marshalling ethnicity, religion, culture and national identity to build these publics in the first place. An exhibition in Indonesia illustrates the collusion between civil society groups and the police. An art exhibition by PLU Satu Hati and Independent Art Management (IAM) in Yogyakarta led to an attempt by a hardline religious group, Laskar Kasimodo to forcefully take over IAM’s office. Laskar Kasimodo claimed that the exhibition had a LGBTQ agenda. The police were called, but instead of detaining members of Laskar Kasimodo, they confiscated several artworks they deemed controversial.

Nor is it always possible to trace the chronology of events and identify which agent sparked the sequence of violations when relying on resources available in the public domain. Further, identifying which party caused the most damage can be subjective. This multi-agent facet of suppression is best captured in close analysis.

To illustrate, The Third Wife (Vietnam, 2019) by Ash Mayfair is a film about a 14-year old girl who becomes the 3rd wife of a rural landowner. It was approved for release by The Bureau of Cinema. After its premier, a public debate raged over the lead actress, who was 13 at the time of filming, appearing in ‘suggestive scenes’ in the film. Mayfair explained that she had the actress’s mother’s consent, and used an all-female crew during the filming of sensitive scenes. This did not placate netizens, leading the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism to instruct The Bureau of Cinema to re-examine the film and its licence. Before any action was announced by the Bureau of Cinema however, the producers withdrew the film themselves, saying they were doing so due to “pressure from the press and public opinion,”. Subsequently, the film crew was fined for screening a different version instead of the one licensed by The Bureau of Cinema before release.

This case also demonstrates the complex interplay between the public and the state which can derail the release of works that have already passed existing state vetting.

Within the scope of this report, it is not possible to untangle the sequence of events, nor the relationship of power and influence between these different agents of repression in detail. However, the data does pose an intriguing question: Would many of these works have been proscribed without the input/instigation of these secondary agents?

Why – Breaking boundaries

A single work might face multiple sets of accusations at the same time. The rhetoric of harm, insult, damage, immorality and danger were frequently used to attack films, books, art and other cultural products and events. In analysing these myriad reasons, a recurrent theme of breaking boundaries emerges. A ‘natural’ consequence of which is to maintain boundaries – by containing, removing, limiting, or punishing.

These boundaries might be societal norms, political orthodoxies, culture, tradition, religion, gender or sexuality. But the salient point is that these are borders that are imagined, fluid and changeable. The way that a society reacts to a work of art reveals more about the fissures and anxieties of that society than the work itself.

As noted by Carol Becker, “Artists do not create volatility even if their images trigger it. Such turbulence already exists in society…the work merely creates a point of cathexis – a location of de-territorialized emotions4.”

Moral policing

At 62%, the most common reason for violating free expression in the arts came under the umbrella of moral policing. Violations were enacted against works or events seen as having transgressed received ideas of morality, religion, culture, ‘feminine’ behaviours, tradition or ‘good’ taste. Other works were viewed as corrupting or confusing, violent or gory. The discourse surrounding such works were framed as efforts to shield or ‘protect’ the public, pointing to the patriarchal nature of moral policing.

Much of the impetus behind moral policing comes from narrow framings of faith. Yet, formal religious institutions, such as the Catholic church or the National Fatwa Council were responsible for a relatively small number of violations. Perhaps they have successfully outsourced surveillance to their followers. Indeed, one of the most powerful forces against artistic freedom is a public readily galvanised to defend their religious belief system, as these three cases illustrate:

In 2011, following complaints from members of religious groups, the Manila Metropolitan Development Authority (MMDA) removed several billboards and said that there should be an MMDA representative in the AdBoard of the Philippines, asking: “How can it be that we will not contest what is executed at the billboards right now, when we see bulging crotches and excessive voluptuousness?”

In 2016, LadyFast, an arts festival by Kolektif Betina, a collective of women artists and activists in Yogyakarta, was attacked on opening night by a large mob of hardline fundamentalist Islamists. They verbally and physically assaulted the artists and audience members. Women were targeted for specific abuse and harassment. The attackers threatened to burn down the venue, citing the presence of tracts in support of LGBT issues as evidence of moral corruption. The police, in turn, detained numerous artists and attendees for questioning. After the event, artists and rights groups accused the police of colluding with the mob and demanded an investigation.

A Cambodian online series, Tum Teav (2021) presented a light-hearted take on a classic literary romance between a laywoman, Teav, and a soon-to-be-ordained Buddhist monk, Tum. Netizens accused the series of disrespecting Buddhism, harming Cambodian tradition and devaluing Cambodian women. In response to the uproar, the Ministry of Culture and Fine Art forced the performers to apologise, and sign a contract with ten conditions, including allowing the ministry to take control of their Facebook and Tik-Tok accounts, where the video was posted.

Politics

Up to 47% of cases were targeted for reasons that can be defined as political. This includes films, exhibitions, books and events deemed destabilising or critical of leaders. In 2010, Malaysian cartoonist Zunar’s book “Sapuman – Man of Steal” which satirised the former Prime Minister, Najib Razak’s 1MDB financial scandal, was banned; Zunar was also targeted with harassment and legal charges.

In multiple cases, the reasons given could reasonably be seen as a smoke screen. A screening of George Orwell’s 1984, directed by Michael Radford in Chiang Mai was cancelled by a military officer allegedly because the screening violated the film’s copyright. The screening event was entitled “1984: A Society Without Freedom,” and was organised soon after the 2014 military coup in Thailand, pointing to other reasons the military might have been so vigilant in respecting artistic copyright.

Geopolitical

A small number of cases, 9 %, were censored or banned due to geopolitical reasons. These include the banning of the film Methagu in Cambodia in 2021 at the request of the Sri Lankan Government and the removal of monuments commemorating comfort women in the Philippines to protect diplomatic ties with Japan. Malaysia, The Philippines and Vietnam have banned films such as Abominable (2019), Uncharted (2022), and TV series, Pine Gap due the use of the nine dash line, which relates to China’s territorial claims in the region.

Public Health and Safety

Public property, safety or health concerns were cited in 9% of the violations recorded, most of which were pandemic related. While there were legitimate public health reasons to restrict live performances during the COVID pandemic, the uneven application of the rules in Indonesia violated the cultural rights of rural communities to the benefit of the ruling or economic elite.

Some countries used the pandemic to surreptitiously expand the power of the state to control artistic output. In 2020, the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) submitted guidelines for the resumption of shooting films during the pandemic. However, these “safety guidelines” included new regulations on content in film, which had not been included before. The new guidelines tried to expand the FDCP’s ambit to cover areas such as advertising, TV and audio content. Industry leaders condemned the FDCP’s overreach under the pretext of covid regulations.

Liberal causes

One emerging trend is violations committed by netizens or civil society organisations in aid of what can be deemed progressive causes, particularly in the Philippines. In 2015, It’s Showtime, a popular TV series, featured a segment aimed at finding a boyfriend for Pastillas Girl aka Angelica Yap. Philippines women’s rights group Gabriela filed a complaint with the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) alleging the show was demeaning to Angelica Yap. Other cases include TV shows, magazines or exhibitions criticized for fat shaming, child abuse, animal abuse, cultural appropriation and colourism.

These three trends – geopolitical dynamics, health and safety protocols and censorship enacted by stakeholders or audiences traditionally viewed as anti-censorship – are emerging threats which warrant more careful monitoring in the future.

How – Methods

There were common methods used across the six countries, such as legal sanctions, banning, withdrawal of resources. Others, for example re-education, exile, detention, and the intimidation hidden having “tea” with the police, were more prevalent in places like Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand, based on the data collected.

A recurrent feature is the use of more than one method in a single case. Indeed, a case may begin with accusations by netizens, which then invokes a more formal speech act by a politician. This may then trigger the withdrawal of a venue by a jittery arts centre. As the publicity escalates, the press may publish gatekeeping articles; an investigation by the local police follows before the official censor board rescinds its original permit and bans the event.

For example, in 2016, Cambodian actress Denny Kwan was subjected to online attacks by netizens for posing in an outfit deemed too revealing and unacceptable for a Khmer woman. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts invited Kwan for a re-education session where she agreed to dress modestly. However, she continued to post selfies in ‘revealing’ outfits, leading the MoCFA to ban her from the film industry for a year. Any films or images of Kwan were not allowed to be broadcasted or screened for the same period. Thus, Kwan was subjected to online harassment, reeducation, a ban and reduced ability to stay in the sector.

Each of these methods are documented in the data, to accurately capture the multiple methods used to proscribe a work or restrict the creator, often at the same time. The data tracks the different methods used depending on whether the target is an art work, produce or event, a person, or group, or both.

Methods used on artwork, product, event

Full ban, censorship, destruction of work

A full ban, censorship or destruction was used a total of 404 times, sometimes as the sole method, or in tandem with a range of other methods. It was the method of choice in Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia. These punitive methods require significant power to enact, and it is no surprise that the State was the leading agent behind the use of this method.

Pressure/gatekeeping/challenges/accusations

The second most frequently used method employed a range of tools such as pressure, threats, accusations, public statements or gatekeeping. The public was the leading proponent, followed by the state. The Philippines recorded the highest occurrences of this method.

Restricting distribution/access

This method may take the form of refusing a permit to use a larger venue, or increasing the rating to reduce audience access, or removing the work from traditional broadcast (but not from online or streaming distributions). Of the 92 times this method was used, the State was the main culprit. Cambodia recorded the highest number of cases where distribution or access was altered.

Methods used on Individual/Group

Harassment/threats

Forms of harassment or threats were the most common form used against creators and presenters, with over 140 instances recorded. These sometimes came from shadowy, anonymous figures, from a police officer, a junior bureaucrat, from civil society groups or individuals who use social media to harass or threaten artists.

Thai artist Chulayarnnon Siriphol received a death threat on FB because his short film, Birth of Golden Snail, featured a pregnant Krabi schoolgirl who also appears briefly, topless, was seen as insulting to Krabi culture. The film was also removed from the International Contemporary Art Festival Thailand Biennale Krabi 2018 by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture (OCAC), which funded and organised the biennale.

Legal action

Legal action, including fines, or court action were the second most used method against an artist, creator, presenter or organisation, with 72 occurrences. In Malaysia, Seniman, The Malaysian Artists Association filed a police report against a Singaporean performer Nabip Ali, for allegedly insulting the then-Malaysian Prime Minister, a disturbing example of threats and harassment by an arts stakeholder, and also of cross-border attacks.

Physical harm

There were, fortunately, relatively few instances where the creator or presenter faced detention, physical harm or exile. When such methods were used, it was mainly the state which had the power to do so.

However, a disturbing trend has emerged, primarily in Indonesia. In over 20 cases, vigilante groups, often identifying as defenders of religion, morality or even national sovereignty, have verbally and physically abused artists and even audiences at events.

To cite just one example, in 2018, a mob gathered outside the dormitory where Papua students were having a private screening of the documentary Free Papua. The students were accused of being part of the Papua separatist movement. A fight broke out and when the Indonesian police arrived, they arrested mainly the Papuan students instead of the members of the instigating mob.This pattern of mobs using physical violence is a worrying sign of a more dangerous landscape for artists and their rights to free expression.

Response

Because artistic free expression is often violated by multiple parties, using multiple methods, the response from the creators (or presenters) when their rights were violated was equally heterogeneous.

Compliance

The most common response, across the 6 countries, was to comply with the demands of the censorious agent, or find a compromise, with over 376 such instances documented. Commercial cinemas and book distributors rarely challenged bannings, preferring to accept cuts or bans, perhaps out of fear of jeopardising future relations with the authorities. As many of these are commercial businesses, defending freedom of expression was perhaps less of a priority. In contrast, independent publishers, books stores and arts venues did push back, although this was not uniformly the case.

67% of the 652 cases were challenged post-publication, i.e. the works had already been released in the public space when the violations commenced. Significant resources would have already been sunk into the making and presentation of the work; at times, tickets had already been sold to the public. Under these circumstances, artists and presenters often had little choice but to compromise or negotiate, sometimes altering aspects of the work to allow the production or event to continue.

Fear – of harsher measures, or punitive actions – was another clear reason for the high compliance rate. Again, the state as a disciplinary force is indisputable, but there were other points of danger too.

In May 2019, Rapper Chhun Dymey’s song This Society, which touches on a range of sensitive social and political issues, went viral. The Military Police visited Chhun Dymey’s parent’s home and his workplace creating an atmosphere of fear and intimidation. His university threatened to expel him and the hospital where he worked warned him that he would be fired if he continued to write songs critical of the Cambodian government. Faced by these different methods, Chhun Dymey took down the music video from FB and Youtube, saying he did so because “he had concerns for his personal safety and that of his family”.

Defiance

Despite these constraints, it is encouraging to note that the 2nd most frequent response, recorded 175 times, was to fight the violations, proceed in defiance, or withdraw the work rather than succumb to the demands of the agents.

A defiant note was struck by Filipino author Rommel Rodriguez, who took the banning of his novel Kalatas: Mga Kwentong Bayan at Kwentong Buhay, in 2022, as a challenge, saying, “Censorship is my muse. The more an artist or writer is prevented from writing, the more enthusiastic we become and the more we want to write.”

Novelist and academician, Faisal Tehrani, had several novels banned for their allegedly Shiite content in 2015. Faisal, a respected thinker and advocate for artistic freedom, challenged the ban in court successfully. In 2018, The Court of Appeal set aside the Home Ministry’s ban on his four books.

Creative or alternative strategies

There are 132 accounts of artists proceeding using creative strategies or changing the access of the work to get around the violations or active public or community actions in the form of protests, petitions, press statements and other forms of coalition building and push back.

Eight out of 9 works by photographer Phan Quang’s exhibition Space / Limit, (2013, San Art, Vietnam) were censored by the Department of Culture, Sports and Tourism. The artist proceeded with the show, putting up small labels to make explicit that 8 works had been censored. In an environment where artists are often pressured to keep silent about being censored, these acts of creative challenge cannot be taken lightly.

Absent Without Leave (2017), a documentary by Lau Kek Huat failed to get a screening permit in Malaysia for its “communist overtones”. In response, the producers, Hummingbird Productions, released the documentary online for a limited period in 2017 for Malaysian audiences to view, thus reaching the local audience despite an official ban.

Exile or cease making works

Of the 9 cases where the artists went into exile or stopped making work (permanently or temporarily), 6 were Thai artists, pointing to the increasing danger that artists are under in the country since the coup of 2014.

Limitations

The findings shared in this report are drawn from a database of 652 cases, with close to 70 data points per case. While the Pilot has yielded rich raw data, there were limitations and challenges faced by the research team which have some bearing upon the data, analysis and findings.

The ambitious scope of the project – to document 12 years of cases and in such great detail in 15 months – was a daunting task. The work was further hampered by insufficient public records from which to draw the rich data needed. Some countries, such as Malaysia, The Philippines and Indonesia had more readily available documentation, leading to a greater number of violations recorded. In Cambodia and Vietnam, acts of censorship might be more hidden and silenced, which in turn could result in fewer cases documented publicly, thereby affecting the number of cases documented in the database. These are factors that must temper our reading of pure numbers in order to fully understand the reality on the ground.

The heterogeneous nature of violations – multiple agents, multiple reasons, multiple methods and multiple responses even within a single case – meant that there were overlaps in some statistics, and generating clear definitions of reasons, methods etc per case was not simply a matter of crunching the numbers in the database. At times, we were caught between wanting to capture the complicated, slippery force of violations as they took shape in time and space, and a desire for clean statistics and precise findings.

While this project is predicated on quantitative data, there were, as with any research project, aspects of the data mining and entry which were subjective. As has been demonstrated, violations against arts and culture in the region are complex. The official reasons given for attacking a work may hide unspoken agendas; the entanglement of religious, culture, language, ethnicity and politics in all the countries under study can make any attempt to distinguish exactly where the spark point of an incident lies, an exercise in frustration.

The team members at times had different ways of inferring and reading the facts of each case, given our different experiences and contexts. This led to some inconsistencies in recording some data points.

Conclusion

We have worked hard to resolve these issues and have attempted to present the findings in as accurate a manner as possible, given the limitations outlined above.

The Pilot has successfully collected a body of raw data in a previously uncharted field. Using this data, we have built a picture of the key characteristics of violations against freedom of expression in the arts in six countries in Southeast Asia.

This provides a baseline that other researchers can interrogate, challenge and build upon towards developing a nuanced, informed understanding of the landscape of artistic freedom of expression in Southeast Asia,

1 “The Artist as Citizen”, Carol Becker, in The New Gate Keepers by Christopher Hawthorne and Andras Szanto, 2003.

2 This report is informed by only 6 of the 11 countries that make up Southeast Asia. The statistics and findings will obviously change if and when the other five countries in the region are included.

3 Thailand underwent a military coup in 2014 and was under martial law at the time.

4 “The Artist as Citizen”, Carol Becker, in The New Gate Keepers by Christopher Hawthorne and Andras Szanto, 2003.

All graphs and illustrations were created by illustrator, Jun Kit. To learn more about the SEA Arts Censorship Database Pilot, go here. To read about SEA censorship, go here.

This report was edited on 22 Sept to add the name of the Thai researcher.

About the author(s)

Kathy Rowland is the Managing Editor of ArtsEquator.com, a registered charity that she co-founded with Jenny Daneels in 2016. The site is dedicated to supporting and promoting arts criticism with a regional perspective in Southeast Asia. Kathy has worked in the arts for over 25 years, working in the areas of critical writing and arts advocacy, with a special interest in media platforms for the arts. She is the Project Lead for ArtsEquator’s Southeast Asian Arts and Culture Censorship Documentation Project, launched in 2021. She has written extensively on censorship of arts and culture in Malaysia. She was a member of the International Programme Advisory Committee of the 8th World Summit on Arts and Culture, 2019.