“Your art is not Khmer enough!” is not an uncommon phrase given by Cambodian authorities when challenging artists about their creative work. The essentialisation of a perceived ideal and singular Cambodian culture creates a narrow corridor for artists to navigate presentation of their work. But despite this ideal of neo-traditionalism in Cambodian cultural policy, active censorship usually only comes as a reaction to loudly voiced public or political complaints. In politically charged years, these outcries intensify, and the arts suffer alongside independent media, civil society, and opposition politics.

Understanding the nuances of arts censorship in Cambodia requires some contextual background knowledge. The two main actors in this domain are the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts and the Ministry of Information, which are responsible for 40% and 31% of all arts censorship cases between 2010 and 2022 respectively. Ministerial attitudes are often characterised by paternalistic attitude, which are also reflected in many of the countries cultural policies. With the exception of the 2014 National Policy for Culture, culture-related legislation tends to be regulatory and punitive in its policy approach. Cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, is a key policy priority for the Cambodian government and spills over into tourism policy, and identity politics in youth and sport policy.

A not insignificant number of visual and performing artists are employed directly by the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, which enables them to survive in their profession.

Public funds for independent art production are not available despite the technical set-up of a National Arts Fund. The arts sector is dependent on international funding (cultural relation/diplomacy, development industry, philanthropy), corporate sponsors (beverage and telecommunication corporations), entrepreneurial endeavours, and side hustles. The opportunity for earned income through cultural activity is not made easier by Cambodia’s generally weak cultural infrastructure and an only slowly shifting culture of consuming art for free. The space for free expression of the arts outside of political, market or donor constraints, is, therefore, somewhat limited.

Arts Censorship Is Reactive and Often Sparked by Third Parties

State agencies were the most frequent violator of freedom of expression in the arts, responsible for 97% of the cases. However, closer analysis shows, that in 63% of all arts censorship cases in Cambodia, more than one agent was involved, including state and non-state actors. Usually, after a public outcry or the complaint of an institution or powerful individual, the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts or the Ministry of Information (in charge of broadcast media) would take action. It appears that it is easier to appease instigators and ban the artwork in question than to argue for freedom of expression. Even when an initial permit or official support had already been given, it is easily withdrawn if the wrong people feel offended by an artwork. Several distinct cases between 2010 and 2022 illustrate the different dimensions of this behaviour and the various instigators:

- 2015: The North Korean Embassy issued a diplomatic note to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation to ban Hollywood blockbuster The Interview from being screened in Cambodia due to insults to North Korea’s leader, which after referral to the Ministry of Information Cambodia complied with.

- 2016: A pop song about the harsh life of a boxer by singer Khem and songwriter Nguon Soben draws the ire of the National Boxing Federation for insulting the sport (and intangible cultural heritage), following which the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts bans the song.

- 2022: Contestants of the Miss Grand Cambodia beauty pageant wore costumes referencing gambling and were deemed “too sexy.” The Prime Minister, the Ministry of Women Affairs, and several provincial authorities complained about the alleged “degradation of Cambodian women’s values,” prompting the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts to take action against the production company.

Arts censorship, thus, is mostly reactive. Preventive or pro-active censoring rarely happens. In most cases, this is more about politics than actual policy. In fact, most laws have deliberately vague formulation to justify most censorship activity. For example, the 2014 National Policy for Culture forbids anyone from creating or spreading “negative culture”, while the 2016 Sub-Decree on the Management of Film Industry penalises actors in the film sector for “jeopardiz[ing] national tradition, national culture and social morality.” Occasionally, the Prime Minister intervenes directly. His directives are often immediately implemented, even if there is no sound legal foundation.

Pop Music and International Blockbusters Are the Main Targets

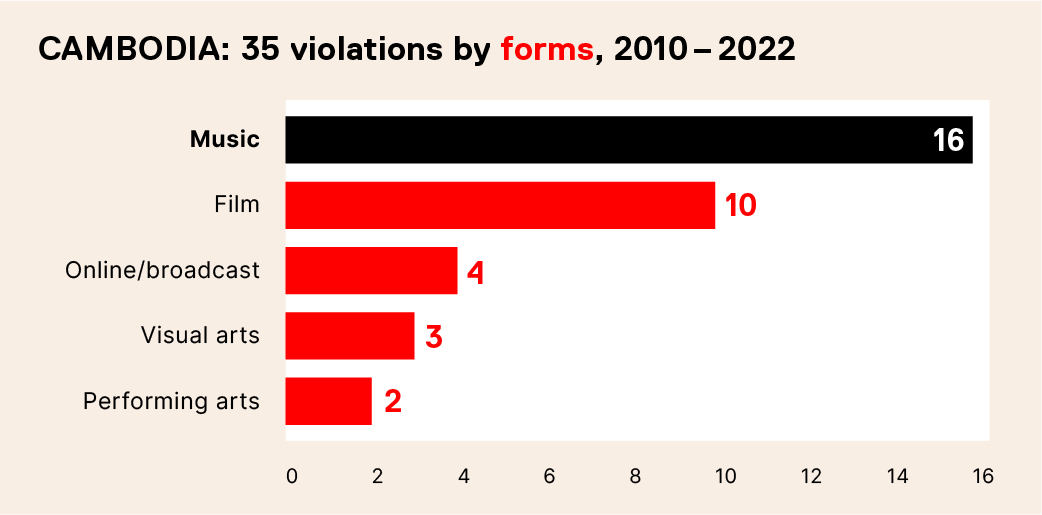

Music and film stand out as the most-censored art forms in Cambodia, with music making up more than half of all censored material – more than in any other Southeast Asian country. Of all the music forms, it is popular music which is targeted in particular. Similarly, most films that face restricted distribution in Cambodia are international blockbuster movies. The attention on these two specific genres is likely due to their mass appeal and wide distribution, and thus their potential to reach large portions of the population. The Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts’ only formal censorship body is situated in its Department of Cinema and Cultural Diffusion, which further emphasises the importance of popular cultural products. Contemporary visual arts, on the other hand, only have niche appeal and are generally of little concern to the authorities.

Only 8.5% of all censored artwork in Cambodia is from the domain of visual arts, which might be due to the fact that contemporary visual artists prefer not to be too present in civil society organising and public advocacy – their often abstract and metaphorical imagery allows them fly under the radar of governmental scrutiny, and they do not intend to compromise this privileged situation. Across disciplines, however, a lot of self-censorship can be observed. Open and direct dissent through creative expression is rare and usually punished harshly and immediately.

Art Is at Risk When National Culture Feels Threatened

A recurring theme in arts censorship justifications is the violation of the country’s essentialised singular national culture, which includes a certain idea of morality. Preservation of cultural heritage is regularly evoked as a reason when contemporary artwork references traditional cultural expressions rather than creating perceived pure versions of said heritage. On the other hand, some contemporary work is labelled as “foreign” and therefore creates a perceived threat to “Khmerness” and Cambodian culture. This logic of purity and tradition extends disproportionally strongly to women whose bodies, dresses, and life choices are often scrutinised and policed by authorities under the banner of dignity and morality.

- 2016: Actress and model Denny Kwan was punished with a one-year ban from acting for wearing clothes that were deemed too revealing by the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts.

- 2015: Contemporary dance company New Cambodian Artists was unofficially banned from performing within the Angkor Archaeological Park for reportedly not being Khmer enough and dressing too sexily.

Perceived lewdness and even vaguely associating Cambodia with a bad image, story or character can lead to censorship.

- 2017: Distribution of British action-comedy film Kingsman: The Golden Circle was restricted due to the film’s fictional villain headquarters resembling the Angkor Wat temple complex.

- 2014: Hollywood blockbuster The Wolf of Wall Street was equally prohibited from being distributed in Cambodia for its large number of sex scenes, nudity, and profane language.

Of course, political arts censorship exists, too, even if not as frequently. These cases might aim to silence fearless rappers criticising government policy or appease foreign governments such as Sri Lanka and North Korea.

Political Skittishness and Growing Authoritarianism

Between 2010 and 2022, a total of 35 public cases of arts censorship were documented. The highest number of cases were recorded in the years between 2015 and 2018. These years saw not just the assassination of a famous political analyst and an (unrelated) arrest warrant for an opposition party leader in 2016 as well as the forced dissolution of the main opposition party and the arrest of its leader in 2017 ahead of the national elections in 2018, but several newspapers and radio stations as well as civil society organisations were also closed or experienced hostile takeovers. This increase in arts censorship cases in the run-up to a contested national election does not, however, indicate more dissident and political art. Rather, authorities exhibited higher sensitivity to contentious issues and reacted faster and stricter than usual in response to a general governmental tightening of the ropes and control of what art and information Cambodians should consume. To further cement support, many of the targeted artists are asked to come into the ministry for a re-education session and urged to publicly apologise for their ‘mistakes’.

Politicised Neo-traditionalism Informs Arts Censorship in Cambodia

The central pattern in Cambodian arts censorship is to preserve and promote a singular, heritage-oriented culture, complete with a populist conflation of ethnic, national, and cultural identities and a conservative moral codex that disproportionally affects women’s self-determination. This essentialisation of a “Khmer culture” rooted in what is believed to be ancient and traditional and the cultural policies that seek to maintain a performative status quo make it hard for artists to navigate this narrow corridor, often resulting in self-censorship or deliberate invisibility vis-à-vis authorities. Creativity is often disregarded as ‘foreign’ and ‘un-Khmer’, fanning fears of imminent cultural decline.

It is precisely this fear that leads to the almost dogmatic protection of heritage and tradition – tangible and intangible, as well as values and morality. Civil servants and policymakers have experienced an immense loss not just of cultural knowledge but also of the people that guarded that knowledge during the Khmer Rouge regime years. Protecting any remaining ancient and traditional culture appears equivalent to creating an environment of peace and stability. While public opinion is divided on this neo-traditionalist approach of the government, sizable public support cannot be denied. Context is key, not the heritage or cultural expression itself.

The deliberately vague formulations in domestic law around what art is permitted and what is not allow authorities to react to whatever political intensity or populist agenda has priority at any given moment. In political times that are perceived to be more volatile, artistic freedom is suffering from an increase in control and shows of force alongside media freedom, freedom of assembly and political participation, and the right to public information. Seeing how most arts censorship only occurs after public outcry or official complaints from powerful institutions and individuals, however, indicates that it is primarily the politics of the moment that impact artistic freedom rather than a systematic policy being followed to suppress diverse cultural expressions.

About the author(s)

"Kai Brennert is the Founder of edge and story, an evaluation, research and policy consultancy at the intersection of culture and sustainable development. Currently based in Cambodia, he has worked in more than 20 countries across four continents on partnerships, strategy and evaluation in arts, culture, and the creative industries. Kai is also the author of curious patterns, a newsletter that explores current issues and policies in the field of arts, impact, international cooperation and sustainable development."

Reaksmey Yean is an art advocate, an early-career art curator, writer, and researcher. A program director of Silapak Trotchaek Pneik (STP Cambodia), Yean is an Alphawood scholar (SOAS, the University of London for Postgraduate Diploma in Asian Art – in Indian, Chinese, and Southeast Asian Art) and an inaugural SEAsia Award Scholar (2017) of LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore; an Asian Cultural Council fellow (2018), and a beneficiary of Dr. Karen Mcleod Adair grant for MA in Asian Art Histories at LASALLE College of the Arts. He is currently an LL.M. candidate at Royal University of Law and Economics/University of Paris 8 in Public International Law. While his current research is on art restitution in the context of international law, his general academic interest is in Khmerology, Buddhist Arts and Art History.