Duration: 40 mins

Podcast host Chan Sze-Wei leads a discussion on dance-making and dance programming for/in gallery spaces. Joining her are three guests:

Vanini Belarmino, Assistant Director of Programmes at the National Gallery Singapore;

Lim Chin Huat, cross-disciplinary artist and performance-maker whose recent dance work In Her Hands took place earlier this month at the National Gallery Singapore, programmed in conjunction with the exhibition Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee;

Susan Sentler, dance-maker and educator who choreographed Roof Response which also took place at the National Gallery Singapore. It was performed by dance students from LASALLE College of the Arts in August and September 2017 at the Ng Teng Fong Roof Garden Gallery in response to Danh Vō’s sculptural installation situated there.

Stream Podcast 40 on Soundcloud:

Download Podcast 40 here. (right-click and select ‘Save Link As’ on Windows; control+click and select ‘Save Link As’ on Apple)

Podcast Transcript

SZE-WEI: Hi, welcome to the Arts Equator dance podcast. I’m Chan Sze-Wei and today with me in the studio we have Lim Chin Huat, Susan Sentler and Vanini Belarmino. We’re here to talk about dance in galleries in Singapore.

Just by way of introduction, Chin Huat is choreographer and cross-disciplinary artist and educator who directed Singapore’s first full time dance company Ecnad, which undertook many inter-disciplinary and site-specific projects over the years. Susan is a dance artist occupying multiple roles, including maker, teacher, director researcher etc. She has worked extensively in the UK, US and Europe. She has got a special interest in working in galleries where she frequently integrates her own photography and film practice, and has collaborated with visual artists. Vanini is Assistant Director of programmes at the National Gallery of Singapore. She is a curator who’s worked in Singapore, the Philippines and across Europe and Asia, with a particular interest in bringing interdisciplinary projects into gallery settings.

Today, looking at dance in galleries, of course this is not something terribly new. We know that contemporary dance and dance as distinct from performance art has been appearing both as commissioned work and collected work in galleries across the world. We can think of works by Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer, or more contemporary works by Xavier le Roy and Tino Seghal. In Singapore I was looking back and thinking about Lim Fei Shen’s collaborations that she did in the 90s with Tan Swie Hian with his calligraphy and paintings. It seems to me like there’s a different moment in Singapore now because there’s a sense of systematic introduction of performance into galleries that hasn’t been there before. The two galleries I know which are quite active in that at the moment are the National Gallery of Singapore and the ArtScience Museum, which Vanini also programmed for previously, which has a different direction in its programming now but also continues to do so. I’ve also seen performance at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art and some of the private galleries.

I’d like to invite us to take a closer look at what is actually happening here, and what is special about this and what does it mean. I’d love to start with two specific pieces that Susan and Chin Huat made at the National Gallery, in invitation to respond to specific artworks. In Chin Huat’s case, you made a piece called In Her Hands.

CHIN HUAT: Yes

SZE-WEI: Which was inspired by your mum, was that right, with Melissa Leung?

CHIN HUAT: Yes, it’s a collaboration of seven artists, a collective work. Like you mentioned it is inspired by my mum, in a certain way, but when we got invited by National Gallery, we felt the work fit in the environment very well because all those paintings are my childhood. I was born in Malaysia, so all those kampong images and people, hawkers, mothers, are very much like my childhood.

SZE-WEI: These were the works of Chen Chong Swee, right? A Nanyang painter who worked in Chinese calligraphy and painting styles.

CHIN HUAT: Yes.

SZE-WEI: Would you like to say a little more about the work?

CHIN HUAT:: When I walked into the gallery, and when Vanini talked to us about this… we had quite a few conversations with National Gallery last year, we just hadn’t picked a place that was suitable. When we saw that exhibition [by Chen Chong Swee], we said, “oh, that is a place where we can actually set one of a chapter of a complete work to be staged at the end of the year.” That particular chapter focuses more on childhood and mothers, which fit in very well. So we decided to explore on that.

VANINI: Chin Huat also mentioned that he was also trained as a visual artist. That was something that we found quite striking, that he is now performing and that was something that seemed to be coming up with some of the dancers and choreographers that we have been working with.

CHIN HUAT: Because this was similar to my pathway because I was trained as a visual artist before I changed to performing arts. That was my past. So that was how I make that connection, in a certain way. When I made this piece I also wanted to bring my mum to go through my journey to revisit my past. That’s something I can use as a reference when she is here in the piece.

SZE-WEI: That was such a surprise for me when I came to see the show, and Chin Huat’s mum was actually there. We see her at the end of the piece – I got a hint of it because I came early and saw her helping you fix the sewing machine at which you had this beautiful length of quilt that you had sewn, and that you later brought into the gallery with you. You and Melissa were telling stories of your journeys to Singapore to train as dancers and actors, but also looking back in time, I guess trying to look through your mothers’ perspectives of time and what Nanyang might have been like in an earlier time. That was very touching and very beautiful. At the end of it you had your mum, and Melissa had her daughter, walking back to the start of the exhibition.

CHIN HUAT: Actually, my mum didn’t know that she was supposed to be in the show. So the first show she was totally in tears. Later she got more used to it and even helped me to fix the sewing machine when it caused some problems.

SZE-WEI: Could I get you to talk a little about your piece, Susan, which was called Roof Response. This was something that you made in late August and September last year…

SUSAN: It was the last weekend of August last year [2017] and the first two weekends of September, and it was a three-hour duration. I was invited. Mine was completely diverse from [Chin Huat’s]. I came in with nothing. I was introduced to Danh Vo’s installation that he did particularly for the roof garden. I investigated him as artist. He’s quite conceptual, quite political, and in that particular work I was stimulated first by its conversation with the cityscape of Singapore and he was in conversation with that immediately. His choice of materials, that I found absolutely beautiful – he was using Vietnamese wood, and was slotting them in, with a kind of jigsaw-like play in the construction of them. Moreover, he chose this beautiful artifacts that were in marble, that were in contrast so they were almost like embraces, bodily. I almost found in this abstraction between the human, the bodily embrace vs this kind of geometric kind of play. That’s what I played with. I worked with dancers from Lasalle – I teach at Lasalle and was asked to work with them. I selected eleven dancers coming from all different programs and levels. I had nine of them sit outside the entirety of the time, and two of which were situated inside because [Danh Vo] had a small artifact situated in the entrance to the gallery, which was encased in a wood box and was a kind of marble bodily image. That one I played very subtly. I observed it many times beforehand and in fact nobody was seeing it, they didn’t even notice that artifact. There was a sign on the wall that indicated that. When the dancers were there, all of a sudden people were looking at the signage, looking down. They were made curious by the use of the body in collaboration and in conversation with the object and the space. I believe it drew the eye in. Frankly there were actually some security guards who were not notified and in fact they were about to arrest the dancers.

[laughter]

SUSAN: We had to say that they were [performing]. They were doing very subtle activity, just nesting around the area or leaning up against the wall…

SZE-WEI: Hardly moving.

SUSAN: Hardly moving. They were very very still. It frightened the security people – which I adored, I thought that was great, they were like, “What are these bodies doing?” [laughter] Then I thought it was very interesting that upstairs, I think we developed a series of 4-5 kind of movements, I called them chapters or episodes. It was a structured improvisation, so they had space to improvise in the moment. I loved it in that I was thrilled – my whole desire is how can I encourage the spectator to stay, to view, to observe, to notice. I believe the majority of people stayed in that site at least about 20 mins. There was so much chaos that was happening simultaneously the first two weekends with the [Yayoi] Kusama exhibition, which was manic. Upstairs, where mine was nested it was very quiet and zen-like. I was very excited by that. I was interested also in that kind of sensation and mood to be stimulated. I think it did work.

Mind you, this is one kind of work I do – in response to. I really try to think about the space itself, the work itself, the materials of the work, a variety of issues. When I’m doing my own work, it’s more coming from a specific idea that I’m resonating with. Usually in combination with film and photographic stills, sound, objects etc. I must emphasize, I think it’s really important that versus visual art, is this whole sense of authorship versus collaboration. When we work with dancers, or that kind of performing activity, it is multiple voices that collaborate together. I never consider myself as the complete author, in the modernist terminology of “author”. Whereas in a lot of visual arts [the artists] are the first ones to do that. I think that’s where we bump heads a lot. I think when visual artists do use dancers within their work, they still obtain the sense of authorship, not allowing the kind of sharing of making of the work with those dancers or participants, those present.

VANINI: That’s actually quite striking and I want to respond to it. That happened to me some years ago. Most of the work I have been doing is collaborative. So this question of authorship. We did this project more than 13 years ago where the choreographer stayed with a visual artist for about week. This was an exchange of ideas about life, about the way of working. Until such time that the visual artist developed a painting based on this one week exchange. This painting was sold to a collector and ten years later there was a show, a retrospective on this particular artist, and it was sold as a body of work to a commercial entity.

SZE-WEI: Including the performance component?

VANINI: I just found out that the videos that we worked on collaboratively were used for this particular show. I find it quite touching, really striking that you point this out how you also specify your particular work and your authorship for your work, even film and photography, as opposed to being a choreographer.

SUSAN: It’s shared, as far as I’m concerned, because it’s a collaboration. If I were the performer, as well (I’m not, I work with others)… I think in dance we have an immediacy of understanding that shared kind of making.

SZE-WEI: I think for certain enlightened choreographers.

SUSAN: [laughs] No very true. I think there was a past situation when that did not come into play.

SZE-WEI: That’s changing now.

SUSAN: Thank you. But it’s very prevalent today. But we are even now hitting obstacles left right and centre on that with ones who are more intelligent and know that, we’re still hitting obstacles with that.

SZE-WEI: Perhaps I could invite Vanini to say a little, maybe for a start from your perspective as a gallery programmer. It’s a very specific choice to invited performance or interdisciplinary work into the gallery in this format of response. For both of these pieces I see that it’s framed this way. You did tell me that it’s a bit different with Chin Huat because your seed of an idea came before you came into contact with the Chen Chong Swee collection in that gallery. But the decision to frame the inter-disciplinary work that comes into the gallery at the moment is usually with regard to an existing piece of work. What struck me also with the Danh Vo and the Chen Chong Swee pieces or exhibition, was that it wasn’t really possible for Susan or Chin Huat to collaborate with them because Danh Vo wasn’t there and Chen Chong Swee has passed away, hasn’t he?

CHIN HUAT: [laughs] Yes.

VANINI: For the gallery we actually do want to provide this new entry point for the public. Interestingly, like what Susan mentioned, this particular artifact of Danh Vo which was at the entrance of the gallery would normally not have been noticed, because it just looks like a marble, sitting there. For the bodies to accentuate the work and to provide attention and give another perspective to the public in experiencing the work – I think that there is this idea of slowing down. Normally everyone is busy. The gallery is so porous, I mean you have two buildings merged into one, and you are actually trying to figure out how to find your way. But providing these new entry points, we try to capture people who probably wouldn’t normally take notice of the art, or wouldn’t have come to the gallery, to provide a different sensation. The longer strategy of course, is that we have these three tiers of audience that we would like to target: Those who have not come to the gallery, those who are already interested but how do you encourage them to come back, and those who are specialized audiences, whether specialised museum audiences or music enthusiasts, dance enthusiasts or new media enthusiasts, and so on. So by providing this other layer you see the works in a different light. So for instance to see the work of Danh Vo through this choreographic piece, Roof Response, or In Her Hands which used three different languages – apart from bodies they also used text. We also have poets who respond or re-imagine particular pieces and the lives of artists. Different artists have different ways of responding to it. Hopefully this will provide another layer of confidence for the public that there is no right or wrong way of reading a work or experiencing an exhibition.

SZE-WEI: I think what’s so beautiful about performance work, whether dance or theatre or other forms where have physically embodied performers in the gallery, is that certain impact for a gallery viewer. An audience who is there in their bodies, with the presumption that an artwork is something that hangs on a wall or is a static piece of sculpture, that suddenly takes on another human embodied moving dimension. That makes you relate to the work in another way. I am thinking now of Melissa [from In Her Hands] sitting in front of the painting of the lady in red and herself also in red, kind of creating another depth to the landscape and the time.

CHIN HUAT: For In Her Hands, our work was working with the theme of mothers. Working in the gallery actually changed a bit of our original idea of how we wanted to set the piece. We did in fact actually get inspiration from the paintings of Chen Chong Swee. [There are] a lot of things we might not think about when we get into the gallery, we respond to the paintings. A lot of people might not be aware of all the details of the paintings. We are the ones who tried to bring out the detail of certain selected paintings. So we tried to imitate what is similar to what we actually went through, to make audience remember such images in the gallery.

VANINI: Also for the performer there’s another layer because they are not performing on stage. The proximity, the access of the audience is really this close. This provides another layer of experience for the artists that we work with. Hopefully it opens up another way of working, like what Chin Huat said.

SUSAN: I know you’re probably going to flip here, but I’m going for it.

SZE-WEI: Go ahead.

SUSAN: I think it’s the idea of dance going beyond response. Those kinds of works, and there’s a whole host of them, works whose site is not the proscenium stage and may not be site specific but is desired to be in the galleries or museum per se. There’s a certain kind of habitus that yields for certain works. I think we need to encourage programmers to look into that. I gave a talk for the Asia Art Archive two years ago for Art Basel – there was a call out for talks – [mine] was entitled “New Dance Politics/New Politics for Dance” and I subdivided exemplaries of ideas of body as source, body as archive, body as architecture, body as facilitator or participant, body in response (which is the ones that we are talking about), and body as political. Also, you can talk about the body as material or element within cross-, trans-, multi-, inter-disciplinary works. There’s a whole host [of such works]. If you look at Tino Seghal, his work is completely devised by bodies and he calls his performers participants. Again, different people have different ways of attributing who [the performers] are. It’s in a specific gallery museum site, a public site. The whole work is manifested in the body, not in response. (Though may be These Associations was in response to the Turbine Hall [of the Tate Modern in London], it was built upon that.) I think we really need to start considering, urging gallery sites and museums to look into these kinds of works because they are just as prevalent and necessary, and not just as a tag on. As complete work itself.

CHIN HUAT: It brings up an interesting thing. When I started to create work to bring people to galleries or sculpture gardens, all this, was to create a flow, to bring people to watch an art piece or artwork, or bring dance or performance closer to public. All these were special performances that happened in public spaces or unconventional set ups. I think that it was more interesting for some publics. It created attention and awareness. Also, people who don’t really walk into a gallery. Through all these activities they get to come in and experience what they never go through [before].

SUSAN: I’ll be devil’s advocate to that. This was one of the things brought up in the talk, by Anna Chan who runs [West] Kowloon [Cultural District]. If it’s just a matter of situating the piece inside a gallery for that sake but it’s not really addressing the work or the needs of the work, is that appropriate? I don’t think it is. I think we need to really consider those people, those artists and works that manifest themselves in particular sites and the work itself becomes more visible because of the nature of the site. It’s not just a matter of transplanting.

SZE-WEI: Vanini would you like to jump in here? Also from your experience of working as a curator in so many more settings than just the gallery.

VANINI: It’s always tailor made. The gallery’s a very demanding space, to be honest.

SUSAN: Oh of course.

VANINI: It’s demanding from all directions. It demands a lot from the performers and the choreographers themselves, because it’s a new type of encounter. It’s interesting that you talk about the audience encounter because not all audience appreciate it. There’s still in the process of orienting the pub and having them understand that the body is not just an object. It’s a process and another way of experiencing the work. It’s not just something to take because you know, now it seems too important to “take” an image.

SZE-WEI: To take a photograph, you mean?

VANINI: To take an image, to capture everything.

SUSAN: They don’t even look, they don’t even notice, they just shoot.

VANINI: This slowing down process. I think it’s called to slow down a bit. That’s why we try to integrate performance.

SUSAN: [Juhani] Pallasmaa speaks about it. In this talk I ended with a quote from one of Pallasmaa’s books, “In a culture where time vanishes or is exploded. As in our age of speed the task of art seems to be to defend the comprehensibility of time, its experiential plasticity, tactility and slowness.” So in other words, it’s our responsibility.

CHIN HUAT: In response to that, when I first brought people to connect with the visual arts – in the 90s, when Singapore first started to become more urbanized, people hardly stopped and appreciated an art piece. During then, my intention was just to slow people down, to stay there, and to appreciate the artwork. So I created dance pieces with all these art pieces.

VANINI: To be honest, we are lucky to be working in this environment. For instance, in National Gallery Singapore, we do have very cooperative colleagues. Our curators are also quite open. They have opened the doors of the exhibition spaces to us on the programmes team to work together. There’s also a genuine interest to work with artists from Singapore, Southeast Asia and beyond, obviously.

SUSAN: But I think of course again, it’s also not looking at it in a specific lens, as response. That is just one way.

VANINI: I agree.

SUSAN: It’s investigating works also that stand on their own. Then again, the tricky thing is for the maker of the work in conversation with gallery, with the producer, with the curator – what are the needs of the particular work. What is the duration, what are the particular needs of the performers. Once again, they aren’t an object, so therefore they need a resting place, they need certain rotas of how to deal with it. They may need certain other facilities. I am coming back to the Hayward Gallery to work with Josiah McElheny’s work.

SZE-WEI: This is in London?

SUSAN: Yes, in London. I already did [this work] at the White Cube, at the Whitechapel Gallery. They’re so fantastic. This time they really want the whole four months, activating his works which he calls “costumes”. They’re very heavy, very precarious. He wants contemporary dancers doing this and I’ve kind of been with this. It’s interesting, they’ve already said we’re going to employ osteopaths and masseuses. I said “Thank you!”

SZE-WEI: That’s amazing.

SUSAN: They came to me and said “Should we?”, and I said, “Yes you should.” When we worked with Tino Seghal on These Associations it was three months ongoing. After the first couple of weeks they came to me and some of my other colleagues and said “Help, people are getting injured left right and centre, what can we do?”. Again we hired two osteos who were coming in full time Wednesday and Friday and were seeing people back to back. It’s taking on this sense of responsibility, what do you need to support the body?

SZE-WEI: What is the infrastructure that is needed?

SUSAN: Very good.

VANINI: The museum is not really built for that. We did however do two pieces that are standalone, with Lee Mingwei – not on dance but on opera – we had Sonic Blossom run for 21 days at the gallery. It was challenging because the gallery is not a performing arts space -but it’s also not an excuse not to stage stand-alone works like that. It was there and it was quite interesting to work around certain rules, for example vocalizing as a singer. You just don’t say it, you go to the bathroom and you vocalize if you have to. We had a six hour performance for 21 days.

SUSAN: This is where I came into dispute at the White Cube, because they had a green room on the opposite side of the square. It’s January and it’s raining and snowing in London. I had to fight with them to allow the dancers to stretch afterwards. It was excruciating to have these 25 kilos on their shoulders. Afterwards when they allowed me to do it, if anything, the people who were visiting the exhibition loved it because after [the performance] they had time to converse with the dancers about how it was to embody these costumes, what it was etc. They realized it was another layer of communication that the invigilators could not provide to the public but the dancers could.

SZE-WEI: It almost became another level of accessing the work.

SUSAN: Absolutely.

SZE-WEI: Just listening to the talk about site and costumes, I would like to invite Chin Huat to comment here. [Laughter] Is there any experience you’d like to share from working in settings with galleries and installations? You’ve done beautiful work with costumes. Is there any experience you’d like to share, and some of the considerations that this required because this involved bodies?

CHIN HUAT: One of my signatures is elaborate costumes. I can have an extension of a dancer’s body because I see the dancer looks like a mobile sculpture. It could be in a building or even in a courtyard…

SZE-WEI: Public spaces. You’ve done many works in public spaces.

CHIN HUAT: Even a fountain. I’ve done many works that turned many things alive. I see dancers as a sculpture, in a certain way. It’s interesting when [the audience] sees something out of the frame.

SUSAN: There are many sculpture artists now who slip into performance because of the three- dimensionality of the body.

CHIN HUAT: Yes. Even when I work in a place like a shopping mall, I allow the window displays to become alive. When they open the doors, the mannequins are actually dancers. I bring in metal pieces and paper to become costumes. They become a kind of window display and a kind of performance. They interact with the public. It was my intention starting from the 90s to bring dance closer to the public. In fact most of my work was not staged in conventional theatres. So I explored different types of spaces: architecture, galleries including Asian Civilizations Museum, Substation Gallery, to turn the gallery into a café or have a conversation with the architecture of the building.

SZE-WEI: I think that something that a lot of audience members don’t realise when they see a work in an unconventional setting – they are hit by the freshness of it but I think there’s another layer where they don’t realise the amount of work that’s gone into it from the artist or the curators to be able to adapt this to be possible, to make the circumstances amenable to live performance, to make this sustainable and survivable for the dancers.

SUSAN: Especially a lot them which are more stripped down and it’s just the bodies. People may see it as just, “Oh, well they’re just improvising on the spot”. But in reality to allow that stripped-ness and clarity of what they’re trying to do, the agency that they’re trying to propose on the spectators – that takes a lot of work. Also you have to leave everything open to what happens in the moment, what happens by surprise. That’s part of the beauty of it.

VANINI: Yes.

SUSAN: But you want to keep your performers safe. How do you hold that? It’s really tricky. But it’s crucial now. I think it’s a crucial part of pushing an agency back on a spectator, so that they aren’t just taking a selfie with the object, with the performance or the thing. They are engaging with it and perhaps getting something out of it.

VANINI: Interestingly I had this experience before – this was before, when we starting doing this at ArtScience Museum – because people don’t expect to see performance or dance inside the gallery, they pretend it’s not there. We had this piece, Eko Supriyanto choreographed 20 dancers from Lasalle. They were situated in the different stages of Andy Warhol’s life. I have seen the audiences on a Saturday. Of course the dancers were usually very beautiful.

SUSAN: Attention to how you say “beauty”.

VANINI: I mean that the presence of the body is quite arresting when you have a dancer there.

SUSAN: Perhaps.

VANINI: So you have couples coming in, and guys pretending that I did not see this beautiful dancer moving next to the painting or the artwork. There was some sort of denial that this beautiful body exists in this particular space. I observed this a couple of times when it’s being done inside the gallery. The proximity is different of course when you’re doing it in something like the Chen Chong Swee [exhibition] where the space does not allow this, you’re really confronted with the body. In the case of Susan’s work, you can see it from a distance.

SUSAN: For that one particular work. I’ve been involved in many other works, say for instance with Xavier le Roy. I’ve been involved in the making of his Untitled, where he deconstructs Low Pieces, completely nakedness, it’s in a gallery, we have conversations with people. It’s beautiful. His work mainly deals with transformation and it’s absolutely beautiful. But some people would walk and see it and go away, for fear. Other people, we had to entice them to come in by having these sorts of conversations as well. But there’s all different kinds of… I think it takes time. Going back to the time, not only do we want to slow down time for the spectator, but it will also take time for them to learn to enjoy and grasp and desire this kind of work. Therefore I believe the galleries need to be bold and courageous to start that conversation to unfold.

SZE-WEI: Thank you for that thought. Speaking of time and aspirations on how this could move forward. Building on what Susan’s just said, Vanini, Chin Huat, would you like to share a thought about where dance in galleries might go, in your own wish?

CHIN HUAT: I guess compared to earlier times, we had to break the rules. We had to apply for an entertainment license for every single rehearsal.

SZE-WEI: No, Really?

CHIN HUAT: Yes, we had to write all the way to the minister. I even wrote to the President, to break the rule. We had to engage police to be around because we couldn’t get closer to public in the past. There was a safe distance. They would say how many metres away, and there should be a barricade.

SZE-WEI: Has that changed?

CHIN HUAT: It has changed. Since the first production I did, I broke the rules and fought for it. I am happy to see that the National Gallery now makes it so easy for us, such a luxury. The other thing I would like to talk about is that every time we put on a show like that we consider the structure. How we engage the public, attract their attention. Often we work as a team, including dramaturgs, to look at how people make connections with the piece and the environment, and the exhibition. This is something we went through quite a few rounds.

SUSAN: I think we need to look into exemplaries that are existing today throughout the world such as MOMA, Palais de Tokyo, the Tate Modern, which have particular spaces that allow or are designed with that porosity to allow – be that static works or performative works. And further to what you said, budget. They need to understand that this is work. The choreographers do work, the performers/participants/dancers/whatever you want to call them, if you need a dramaturg, it’s work. I have bumped heads here already with people who don’t understand that, who think it’s just that the desire to make is so overwhelming that they’ll do it anyway.

SZE-WEI: They’ll do it for free.

SUSAN: They’ll do it for free. And yet they’ll pay umpteen amount of dollars for a particular piece, for an object…

SZE-WEI: A painting or a sculpture.

SUSAN: Yes, correct. And that needs to stop right here right now.

[Laughter]

SUSAN: Because for me, especially training dancers at the moment and how to change – I hate the word “industry”, I think it’s “practice” – how we can change this landscape to provide more working opportunities for them. I see this as a really fantastic frontier. But the government needs to look upon it as being necessary, and they need to budget it.

SZE-WEI: Closing thoughts?

VANINI: I think for me, because you said about the wish, the wish is to be able to continue and push this forward and continue building on what we started. What we did with Susan and with Chin Huat is just a starting point. It’s just a layer. Over the years we hope that we can develop extensive work and performance that really is integrated within the building, the architecture. Not just a response, but pieces that are specially, really created for the space and for the public, by the artist.

SUSAN: Artists who work in the spaces. Yes, absolutely.

SZE-WEI: Well Vanini, Susan, Chin Huat, thank you very much for joining me today. I hope this is a conversation that can continue and wishes that can blossom. Thank you.

Performance Photography

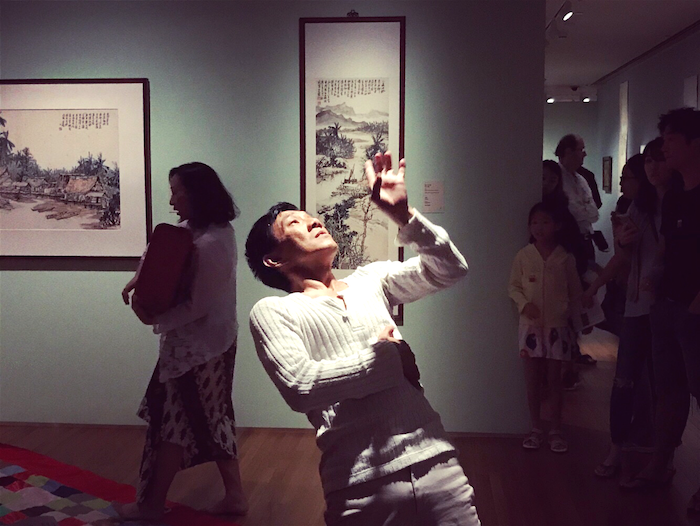

In Her Hands by Lim Chin Huat and Melissa Leung

Roof Response by Susan Sentler

In Her Hands, performed by Lim Chin Huat and Melissa Leung Hiu Tuen, was created in collaboration with Dorothy Png, Pearlyn Cai, Tennie Su and Yong Rong Zhao. It was dramaturged by Danny Yeo. The performance was in Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien, and was inspired by (and programmed in conjunction with) the exhibition Strokes of Life: The Art of Chen Chong Swee.

Roof Response, choreographed by Susan Sentler, was performed by dance students from LASALLE College of the Arts, response to Danh Vō’s sculptural installation at the Ng Teng Fong Roof Garden Gallery. It was performed on three consecutive Saturdays, 26 August, 2 September and 9 September.

Podcast Host Chan Sze-Wei is a dance maker, performance maker and sometime trouble maker. Blending conceptual, interactive, improvisatory and cross-cultural approaches for theatres, public spaces, performance installation and film, her work is often intimate and sometimes invasively personal, reaching for social issues, identity and gender.

Podcast Guest Vanini Belarmino joined the National Gallery Singapore as Assistant Director (Programmes) in November 2016. Her curatorial interest focuses on the productive potential of encounters by identifying and facilitating collaborations between artists across genres. The resulting works create new experiences by situating the body as an object in a museum or public space. Prior to the Gallery, she worked as an independent curator, producer and writer, and developed art initiatives in Asia, Europe and the Middle East. From 2011 – 2013, she curated the artistic programmes for ArtScience Museum at Marina Bay Sands’ blockbuster exhibitions and was commissioned to curate site-specific and durational works for the inaugural year of ArtScience Late, 2014-2015.Vanini received academic training in theatre arts, art history, European cultural policy and management. She was a recipient of the Asian Cultural Council Fellowship in New York City in 2014.

Podcast Guest Lim Chin Huat is a cross-disciplinary artist who has over two decades of experience in capacities as creative director, visual artist, performer, dancer, choreographer, costume designer, facilitator and educator. In particular, Chin Huat is known for his stunning visual creative works with cross-disciplinary, site-specific, outreach and non-conventional in nature. Chin Huat has worked with Toy Factory Theatre Ensemble (1990-1996), and later, as co-founder and artistic director with ECNAD (1996-2013). He is working as a project creative director and consultant since he ended his his 17 years full-time career with ECNAD. Chin Huat is a recipient of the Young Artist Award (2000), and a nominee for the Spirit of Enterprise Award (2004). Chin Huat holds double Diplomas in Dance and Fine Arts from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. He is currently part of faculty of movement with Intercultural Theatre Institute since 2015.

Podcast Guest Susan Sentler is a dance maker/artist working as a choreographer, teacher, researcher, director, dramaturge and performer. She has taught globally in the field of dance for over 30 years. Susan’s practice is multidisciplinary with a distinct focus on gallery, and museum contexts. Within these sites she creates ‘responses’ to specific visual art works and exhibitions as well as durational installations using objects, sound, moving/still image, and absence/presence of the performing body. Her work has been exhibited and performed in the UK, USA, Europe, and Asia. Currently she is a Lecturer of Dance at LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download