By Nabilah Said

(1,800 words, 6-minute read)

I’ve never actually attended the Bangkok International Performing Arts Meeting (BIPAM). This year, the pandemic allowed me to, as BIPAM offered a five-day digital programme full of showcases, talks and other activities. It brought me, a Singaporean, a world of imagination – colourful and joyous in parts, provoking me with this year’s theme of “ownership” and the possibility of creating a more promising and inclusive future. Yes, it also spoke of dark histories, inner demons, shaded with the twin spectres of COVID-19 deaths and socio-political unrest in the rest of Southeast Asia.

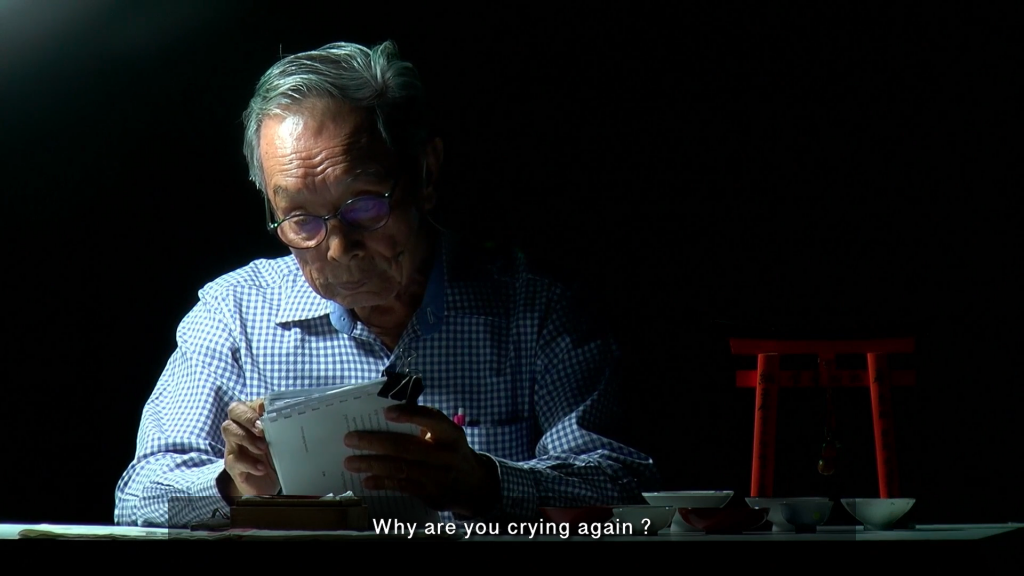

My introduction into the world of this year’s BIPAM came in the form of a charming and ambitious performance lecture, An Imperial Sake Cup and I, by Thai historian Dr. Charnvit Kasetsiri. Starting from a sake cup he received from the then-Japanese royal couple as part of a work event in 1964, Dr Charnvit delivers a sprawling history lesson that unearths the various ways his personal history intersects with that of both Thailand and Japan – for example, he talks about the building of the Death Railway, of which his hometown of Ban Pong is a southern terminus, and notes drily that “most tourists don’t have memory of war or suffering”. The script, co-written by Dr Charnvit and Jarunun Phantachat, covers a lot of ground, ranging from a history of the imperial house of Japan, to where the best water for sake can be found (Fushimi). There is even a close-up of a sake cup bearing erotic figures, which made for a cute contrast with the buttoned-up academic.

The performative elements of An Imperial Sake Cup and I deliver mixed results (in a separate panel, Dr Charnvit admits with a laugh that “I always do lecture, I never do performance”), but is ultimately saved by the 80-year-old’s earnest presence and assistance of the stage crew for costume changes, voice acting and even shadow puppetry. I appreciated Dr Charnvit’s stories more, which offered enough hints of emotion to leaven the more dense bits of the show. For example, he swore he would never speak Thai again when he left Bangkok for Kyoto in 1977, accused of being a communist and plagued by a government massacre of student protestors at Thammasat University on 6 October 1976. Punchy multimedia rounds out these moments, especially for an audience unfamiliar with Thai history. The performance lecture manages to end on a convivial note, with Dr Charnvit sharing a sake toast with the audience.

I then dove into the deep waters of arts censorship with Deleted Scenes in SEA, dramatised readings of three plays which have never been performed publicly or had their performances halted in their countries due to censorship: Suksesi (Succession), a 1990 Teater Koma satire of political succession in Indonesia, written by playwright Nano Riantiarno; History Class, an imagining of history class in a utopian future, written by academic Prajak Kongkirati; and INSURGENCY by Singaporean playwright Elangovan, from his banned series of short plays from 2006, SMEGMA.

This curation of plays is a programming triumph. The internet, in some ways, is still ungovernable, and hence is the best stage for work that seeks a freedom they were once robbed of. I liked that their respective histories of censorship are spelt out at the start of each performance, details about arrests and interrogations not allowed to be forgotten and subject to scrutiny by today’s audience alongside the plays themselves. Sometimes, these were self-initiated—in a panel, Prajak shares that his play was ultimately pulled from performance from a showcase by Thai theatremaker Wichaya Artamat. Details were sparse, but one could assume that it had something to do with artist safety.

But what pushes this programme into a more inspired realm is its regionality, powered by the collaboration between BIPAM and the Indonesian Dramatic Playreading Festival (IDRF). The decision to pair each play with directors and performers from different Southeast Asian countries unearthed rich cross-references and startling regional similarities.

In the hands of Indonesian director Irfanuddien Ghozali, History Class plays out in an online classroom in 2057, with students recalling the horrors of Thai “past” in Bahasa Indonesia. Barring explicit descriptors (“smiles were restored to Thai people”), the difference in setting was depressingly imperceptible. Monochrome photos of police brutality flashing on screen could have come from any number of countries in the region. While the playwright ultimately works himself into a dialectical corner—this was his debut work—the play did offer a somewhat hopeful note on the future, which was brought to life with Irfanuddien’s inclusive and poignant casting: the performers included transwoman and writer Jessica Ayudya Lesmana as the teacher, Svetlana Dayani, a real-life survivor of the Indonesian genocide of 1965, as a student, and there was also a deaf student and interpreter.

In Thanaphon Accawatanyu’s version of Suksesi and INSURGENCY, which bookended the readings, he manages to create an aesthetic experience for both plays akin to a shared cinematic universe. One recurring motif is the iconography of a sweet, which peppers the frenetic, emoji-ridden world of Sukseksi, bringing out its themes of corruption and nepotism. In the black-and-white world of INSURGENCY, this motif, emblazoned on the two soldiers’ hats, fades into the background as the play’s violence comes into sharper focus. Suksesi, with government minions and the wealthy portrayed as a series of comical dog gifs and barking dolts, is a biting send-up of power (it was banned under Suharto’s government) but, as it was not read in full, ends rather abruptly.

INSURGENCY was a powerful closer. Elangovan’s most potent plays have had more longevity as published works rather than staged ones. His play about marital violence in the Indian Muslim community, Talaq, was denied a performance license by Singapore authorities in 2000. In INSURGENCY, Waywiree Ittianunkul and Saifah Thantana, both of whom were in Sukseksi, play a cruel soldier and a female captive, while a younger, less jaded recruit (Thanaphon himself) figures out just how hellish the world can be. No violence is ever shown – most of it is indicated in stage directions flashing on screen, and yet I found myself with a lump in my throat for most of the play.

Elangovan’s script is economical yet brutal, while the film’s quick cuts and stylised choices (a handheld humidifier is used as a gun in one shot) create a real sense of dread. The design for INSURGENCY is the most cohesive and impactful of the trio of readings, especially the use of a haunting Southern Thai nursery rhyme, Krai Nor, at the start, its notes shrill and discordant with the setting (production design: Jenwit Narukatpichai, sound design: Theerapat Wongpaisarnkit, editor: Nattawoot Nimitchaikosol). The team choose to pixelate the woman’s face, which dehumanises her, though no more than the play’s overall theme of the unjust senselessness of evil against an oppressed minority. Yet Elangovan does not leave us totally bereft, as one soldier clings desperately to a thread of his conscience, the woman cries out against brutality in a final, rousing monologue.

‘B O R R O W’ was based on a simple premise: Put an individual in an all-white room. Ask them questions. Yet director/playwright/set designer/performer Dujdao Vadhanapakorn manages to create a surprisingly powerful piece shaped by a series of intriguing prompts. For example, in one section, she asks her performer-respondents to lie in each of their answers (in response to “What is your gift in life?”, one person replies: “To have parents who understand my feelings”). It helps that she chooses two pairs of related individuals, a mother and daughter (Kru Toi and Lordfai), and two brothers (Stang and Tamp), which allows the piece to unravel quite dramatically, giving the audience just enough character reveals and hints at complex dynamics and internal angst, as well as hitting emotional highs and comedowns.

One of the most effective provocations in the piece is the set. A mound of snow-like substance dominates the white space, inviting the performers to mold and change it in relation to their bodies. Yet, as the piece enters into more emotional terrain and the performers grow more introspective, the space becomes oppressive. One performer starts off sitting on a chair at the top of the mound, and later ends up crumpled on the floor at the edge of the room. ‘B O R R O W’ works particularly well as a video piece, with slick editing (Manussa Vorasingha and Aekkarin Thungrach) and beautiful cinematography (Waritpol Jiwasurat). Dujdao and team mute the audio for several sections of the piece, a choice that is both kind and responsible, and also shows her awareness of the true power of the piece – a vulnerability that goes beyond words.

The most fun programme of BIPAM comes from an “unfun” source: Google Documents. A Perfect Conversation by Sasapin Siriwanij (BIPAM’s Artistic Director, also known as Pupe) and Singapore performance maker Eng Kai Er was a low-stakes, easy conversation about two of their past works—Pupe’s Oh Ode (2017) and Kai’s Blunt Knife (2019)—which unravels on the collaborative platform. Audience members are able to join in their written chat and respond to one another, the conversation gently organised with some reflective questions led by each artist. I enjoyed being able to learn about Oh Ode, via a short video snippet of Pupe being sculpted live into a “perfect being”, her body frozen in a traditional Thai dance pose. She recalls how Thai audiences reacted to her initially bared breasts – “only after my nipples were covered could we all return to peace again”, to which someone responds “Nipples Power!!!”

I had caught Kai’s confessional solo show, Blunt Knife, back in Singapore. While the piece is not easy by any means (if you want, you can read more about it in Corrie Tan’s reflection for ArtsEquator) and impossible to sufficiently unpack within the shared BIPAM event, I did appreciate that A Perfect Conversation created an opportunity for the artist and us to revisit the piece with the benefit of some distance. The session was closed off with a live dance party to the sounds of disco-pop tune Dancing Queen by Abba. This crowdsourced song option was a poetic ending for an afternoon conversation with two artists who use their bodies expertly as vessels, canvases and provocations for art.

I ended my BIPAM experience with a short performance titled Pieng Buhn (Wings), with performer Kam Nainual sharing her story as part of the Dara-ang ethnic group, and her people’s history of migration from Myanmar to Thailand in the 1980s. Speaking in both Thai and the Dara-ang language, Kam carries herself with quiet dignity, singing songs about their courtship rituals and explaining how their traditional costume is meant to show how they are “Nang Doi Ngern”, or “angels from heaven”, while also recounting the unjust treatment they receive as ethnic minorities in Thailand, as many of them are stateless.

What BIPAM gave me was a journey of manifold ambivalence, of precarity, of politics and danger lurking at every corner. Yet, it also gave me—dare we think it or even say it aloud?—hope. That hope was found in the shared histories and resilience of the people of Southeast Asia, and how these connections were explored through the various BIPAM programmes, including dialogues and panels I did not manage to check out, and also in Under the SEA, a series of regional dialogues held as part of BIPAM in 2020 which can still be accessed on demand. It was also in the spirit of community fostered within the shared virtual world of BIPAM 2021 housed in Pheedloop, which featured chat boxes and photobooths for informal interactions, and easy navigation of both live and recorded events. That hope was inclusive and contained kindness. It was imperfect and demanded nothing.

In Pieng Buhn, we see a tiny figure of an angel in Kam’s hands that have seen so much. Against a single source of light, the angel grows giant shadow wings that loom large on the wall. It is menacing in its own way. When I see this, I finally understand the BIPAM theme of “ownership”. It is hope that has wings and body and power. It is hope that we dare say out loud.

The Bangkok International Performing Arts Meeting or BIPAM ran from 1-5 September 2021 online. All photos are screenshots taken by the writer.

Nabilah Said is the editor of ArtsEquator.

About the author(s)

Nabilah Said

Nabilah Said is an award-winning playwright, editor and cultural commentator. She is also an artist who works with text across various artforms and formats. Her plays have been staged in Singapore and London, including ANGKAT, which won Best Original Script at the 2020 Life Theatre Awards. Nabilah is the former editor of ArtsEquator.