The Philippines wears its democracy like a badge of honor. It is proof that Filipinos have fought hard against colonizers and dictators, a measure of how we value our freedoms. It is a source of pride, a reason for being: this is what makes us distinct from the rest of Southeast Asia. Our governments, politicians, cultural institutions, and cultural policy invoke democracy to prove that creative freedom is alive and well in the country where free speech is enshrined in the Constitution.

In the context of a Philippines sold as such, a research project that documents 99 violations on artistic freedom across a 12-year period should come as a surprise. How could a country that lays claim to being a democracy, that sees its freedom as its brand, its liberalism as a selling point for foreign investors, be curtailing artistic freedom?

And while it would be easy to think in terms of tyrannical leaders and dictatorial views on culture as the culprits behind censorship, what this research reveals is how acts of censure and the predisposition towards targeting artistic works and practices is not simply about the State wielding its power. Rather, in the Philippines, it is also about religion, as it is about the moral righteousness of public opinion, now cradled—and given more power—by online platforms.

That this research spans the years 2010 to 2022 is important to highlight. To some extent, this tracks the public’s use of social media and its increased relevance in the public discursive sphere across a 12-year period, with this online public’s ever-changing opinions being brought to bear upon artistic practices and cultural portrayals. Note that one does not speak of these opinions to be evolving; at best it shifts from one end of the moralistic pole to another, where reasons for censure actually repeat themselves, no matter that attacks on the arts come from diverse actors and institutions.

Just as relevant is how this research spans two different Presidencies: the liberal-democratic one of Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III from 2010 to 2016, and the populist-tyrannical one of Rodrigo Duterte from 2016 to 2022. This is important because the research lays bare the ways in which this particular change in leadership actually meant new institutions (agencies, offices) being given the power to censor the arts, just as it meant a difference in what subjects and portrayals were deemed offensive or wrong, and as such were deserving of censure. It also, surprisingly, revealed similarities in terms of targeted artists and works.

These two aspects of the democratic landscape in the Philippines are important as these speak to the ways in which acts of censorship have generally gone unchecked, not just because it is undocumented, but also because it has been made to seem “normal.” Across all these attacks on artistic practices and cultural work, the perspective that dominates is one that’s about the State, the Catholic Church, or civil society either seeking redress for what is deemed as “unjust” portrayals, demanding propriety where it is presumed to be forgotten, or imposing moral righteousness upon the artist whose work has been deemed wrong or inappropriate. As such, targeting artistic practices, portrayals, and products are seen to be serving the public good. It serves to protect the citizenry, if not conserve national identity, ambiguous and undefined as those might be. That these will always be in direct contradiction to changing mores, evolving ideologies, and cultural development is what makes acts of censure in this so-called democracy a conundrum worth unpacking.

The Clutches of Catholic Conservatism

As consistently as we claim that the Philippines is a democratic country, we also brand ourselves the “only Catholic Country in Southeast Asia.” And while the Constitution mandates a separation of Church and State, when politicians are predominantly Catholic, and generally seek the support of a “Catholic vote”, what you have is a particular conservatism that permeates our everyday lives.

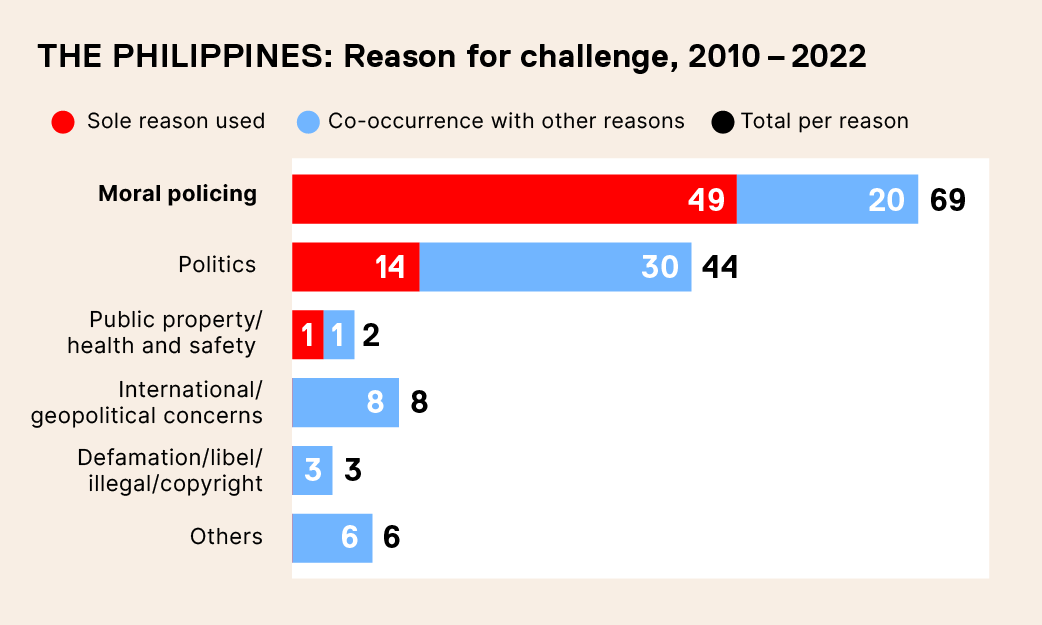

The data the research surfaced does not surprise. The “moral policing” of arts practices and cultural portrayals is primarily tied to a conservatism that is wrought by Catholicism as practiced. This means the attacks on artistic freedom need not always come from the Catholic Church itself. When you have Catholics in government institutions and in positions of cultural power, and when even civil society discourse is dominated by Catholic conservatism, moral policing is practically normalized.

It might be said that the Catholic Church need not do the good work of the Lord here—if censorship is to be seen as such. Because politicians will call to take down billboards that show the whole Philippine Rugby Team clad in briefs because it distracts drivers and is bad for our children; they will take down billboards of female celebrities in sexy swimsuits selling beauty clinics and diet products; they will question any billboard (or advertisement) that to them, as Catholics, is too sexually suggestive.

When one considers this kind of conservatism, it is no surprise that so much of what surfaces in this research has to do with the censure of women’s bodies and voices, both in real life and fictional portrayals. When an actress wears clothes that leave little to the imagination, or allow people to imagine that she’s wearing no underwear; when a soap opera shows a fictional young woman engaging in premarital sex; when female characters have a conversation about infidelity or being a mistress—targeting these articulations and portrayals is about a dominant notion of the acceptable, proper woman whose sexual freedom cannot be talked about or acknowledged.

Case in Point: Two Cases

It is important to mention here two major cases that had the Catholic Church and its Catholic faithful as instigators. In 2010, performance artist Carlos Celdran entered the Manila Cathedral in a Spanish era ilustrado costume holding a sign over his head that said “Damaso”. This refers to the corrupt friar in National Hero Jose Rizal’s novel Noli Me Tangere who oppressed the Filipino native indio. Celdran did this performance-protest at a religious event that had all the bishops and cardinals present, where he also shouted: “Stop getting involved in politics!”. The Catholic Church filed a case against Celdran for “notoriously offending the feelings of the religious leaders and the faithful”, which is penalized under Article 133 of the Revised Penal Code.

In 2011, Mideo Cruz was part of a group exhibit called “Kulo” (“Boil”) at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP). A gathering of works by graduates of the University of Santo Tomas, the Catholic university that takes pride in having National Hero, Jose Rizal as its alumnus,

the exhibit was framed as a critical assessment of the school’s Catholic pride vis a vis the revolutionary that was Rizal. Cruz’s installation, “Poleteismo” (“Polytheism”), exhibited previously in at least two iterations before this one, puts into question the idea of one faith and one ideology. The installation was featured in news and public affairs show “Eksklusibong, Explosibong, Expose” (Exclusive, Explosive, Exposé), which framed the artwork as one that was surreptitiously set-up to critique the Catholic Church’s stand against the Reproductive Health Law.

The backlash was quick and massive, especially after Archbishop Oscar Cruz described the work as “sick and sickening”. It didn’t help that then-President Aquino, a devout Catholic, echoed the same: “There was a depiction of Christ which is not acceptable to anyone and the CCP is funded by public money. It should be of service to the people, but when you insult the beliefs of most of the people, I don’t see where that is of service. Art is supposed to be ennobling and when you stoke conflict, that is not an ennobling activity”. CCP would take down the exhibit, and the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) would file a case against Cruz and other CCP officials under Article 201 of the Revised Penal Code which penalizes “immoral doctrines, obscene publications and indecent shows,” because the “Christian nation has been offended”.

That both the Cruz and Celdran cases happened relative to the battle for the passage of the Reproductive Health Law, is important context. Where women’s sexual freedom and right to choose for her own body are subject, Catholic conservatism—if not the Catholic Church itself—becomes a central character in arts censorship. It doesn’t matter where you mount that performance, or if your art installation is on its nth iteration. What matters is the offense that the Catholic faithful take, and the antiquated laws that give them ways to seek redress.

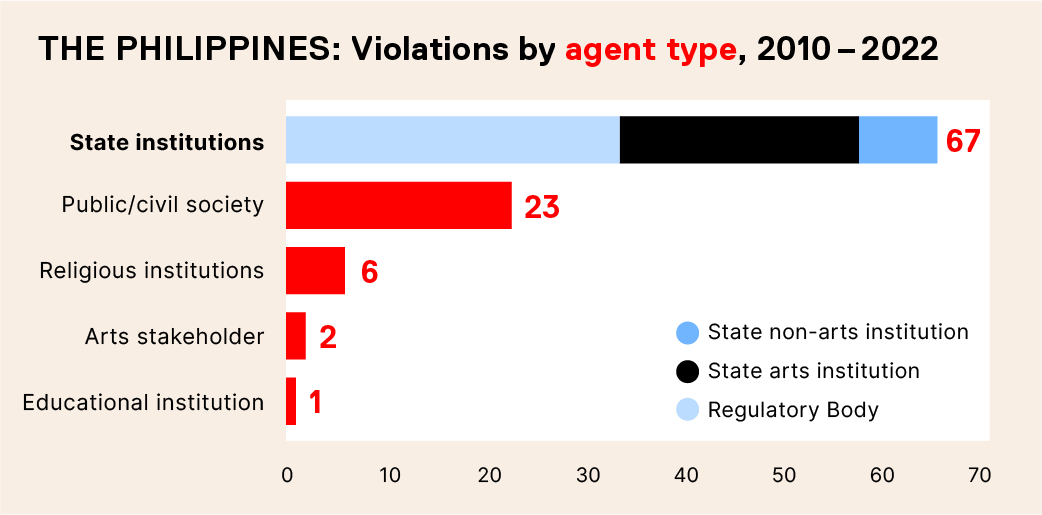

It is worth reiterating here that the Catholic Church does not have to be the main instigator or agent of censorship: in a predominantly Catholic country, other institutions, government and otherwise, including civil society, will gladly and unthinkingly do this work for the Church. This explains why the data shows only six instances in which religious institutions were agents of censorship—State institutions and civil society, so run by Catholics, are actually doing the Church’s work.

Here the research surfaces a basic fact about the Philippines: that while the Constitution guarantees the separation of Church and State, when artistic practices and cultural portrayals are deemed immoral, improper, and un-Catholic, Catholic conservatism as practiced by politicians, government officials, and civil society ensures an unquestioned interweaving of the two.

Regulation As Frenemy of Artistic Freedom

TV and film are the most targeted forms in the Philippines, and the explanation is simple. The Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) exists as a government agency tasked to regulate through classification all TV shows and films before these are made public.

On the surface, one might see regulation to be less about censorship, as it is about ensuring that people are forewarned about whether or not the shows children are watching are appropriate, as it is a way to warn the public that a film is only for specific audiences. This process of classification also allows creators of films and TV shows to backtrack on their work, figure out what to cut out in order to get shown for the demographic they want. To the MTRCB, this is called “self-regulation”, which need not be seen as simply a bad thing—after all, who doesn’t want to “protect” young audiences from content they are not ready for?

The research on the Philippines demands though that we complicate this discussion. Regulation and classification are not objective tasks that simply rate artistic products based on a clear set of standards. There is no better proof of this than the fact that every change in MTRCB leadership means a shift in what’s deemed acceptable or appropriate for public viewing. The more Catholic-conservative an MTRCB leadership is, the more predisposed towards censure of all kinds; the more liberal and educated about arts and culture production, the bigger the possibility that TV shows and films might be allowed to speak of more difficult—violent, sexual, political—subject matter.

Case in point: in 2013 and 2015, two LGBTQIA+ soap operas were aired on television, a rare thing that wouldn’t have been possible under a more Catholic-conservative leadership at the MTRCB. It was heavily monitored though, given a warning from the CBCP about the homosexual content of My Husband’s Lover, and the conversations about infidelity and polygamy on the lesbian relationships in The Rich Man’s Daughter. In those two instances, the MTRCB claimed that it was acting on complaints and concerns from the Church and the general public about both soap operas.

This is where censure becomes MTRCB’s business. Regulation through classification is one thing: it happens before these TV shows and films are made public, giving creatives the opportunity to revise their work if they seek a certain target audience. But when bans and cuts, “suggestions” and “summons” are made after broadcast, MTRCB’s voice becomes that of censor that seeks to protect the public from material that is deemed inappropriate or dangerous, acting as they do as well on complaints from civil society.

Here, the public is treated like children that cannot handle certain content on TV and in film, and are not allowed to have complex conversations about violence and sex and politics. Here, arts and culture seem to be expected to uphold a set of morals and cultural norms in order for these to be released for public consumption. It is also in this exercise that the MTRCB works hand-in-hand with institutions to censure works that are seen to cradle unjust portrayals of say, the police force and the military, or government officials and politicians, or even, films that show the nine-dash line of China, and as such are seen to disrespect national sovereignty over the West Philippine Sea.

This explains how the research surfaced gatekeeping and pressure, challenges and accusations, as the second highest method of censure: the MTRCB is the primary enabler of that exercise.

Here is where “regulation”, Philippines-style, can only be censorship. Not frenemy, just enemy.

An Opinionated Public, A Difficult Defiance

But it isn’t just State institutions, or the Catholic Church, that uses the protection of the public as premise of its acts of censure. Majority of cases in the Philippines are in fact bound to this notion of protecting audiences—especially women and children—from consuming certain portrayals, or from being portrayed in particular ways. This “protection” of course is not clearly laid out, nor is there a checklist of things that the public needs protecting from—which is what makes this kind of censorship even more problematic.

It is in this context that civil society deserves mention. While it stands at a far second to State institutions as an agent of censorship in the Philippines (see Figure 2), alongside Figures 3 and 4, what is revealed is the critical role that civil society plays in targeting artistic practices and cultural portrayals.

While Figure 3 shows how forms that are broadcasted and posted online are most targeted, what it also reveals is the fact of social media platforms (Facebook and Twitter) growing in viability and credibility across the 12-year period of the research, and how these have become the space where public opinion targeting artistic practices and cultural portrayals have gained traction, if not an amount of power. Specifically for the audience that consumes “free” culture, i.e., online materials and TV shows, social media has become a way to air grievances against content that they see, which the MTRCB or other government actors might act upon.

That pressure and gatekeeping tops the methods used to challenge an artwork or event (see Figure 4) is also tied to the civil society that exists as an online public. Here, one sees that across the 12-year period, online platforms have not only cradled dominant public opinion, these have also allowed for the loudest collective voice to turn itself into mob rule that can exert enough pressure, exercise gatekeeping, and mount strong challenges that target artistic work to the point of censure.

As with State institutions and non-government organizations, civil society and the general public as agents critical of artistic freedom don’t come with a checklist of things that artists and cultural workers can or cannot talk about. The Philippines data reveals that what this means is that anything at all can be seen as offensive, or inappropriate, or disgusting at any given time, leaving the arts and culture sector at the mercy of the loudest voice, the biggest mobs, and changing leaderships.

This can only make defiance difficult, shifting as it needs to with the times, dependent as it has to be on whether or not the artistic product is a source of livelihood, or is at the mercy of big capitalists that need to recoup investments. The political climate is also important to consider, as shifts in leadership in regulatory institutions and cultural agencies, and the tenor and voice that dominates public opinion on social media, dictate how creators and presenters might decide to handle being targeted.

This is where the data is important. Compliance and negotiation will top the list of responses because it is how censorship has become normalized in the Philippines, where government agencies can claim that there is no censorship because what we have are conversations that give artists the opportunity to revisit or revise material, or make amends for unacceptable articulations, performances, and portrayals. While defiance and counter-challenges from the arts and culture sector are a close second, it is important to see this relative to the data on media and public support for the targeted works or artists. The years of Aquino reveal stronger support for the arts and culture sector and a seeming fearlessness in counter-challenging acts of censure. With the climate of fear during the Duterte years, as well as the deepening echo chambers on social media, divisiveness in the public sphere and the arts and culture sector made resistance more dispersed, if not one that was quick to dissipate.

In Place of a Conclusion: A Conundrum

In the Philippines, restrictions on artistic freedom have less to do with a fixed set of rules that need to be followed, as it is more about the lack of expressed rules that draw line(s) that cannot be crossed by artists and cultural workers, creators and presenters. As such, that line that’s crossed could be about anything at all—maybe being critical of or poking fun at Catholicism, maybe a conversation about sex or sexuality, maybe the display of (mostly) women’s bodies. Often enough, it is about violence and gore, and the unjust portrayals of people in power. In the years of Duterte, activist works and artistic work that were presumed to speak of drugs were heavily targeted—a by-product of Duterte’s policies against drugs and the Philippine Left.

That this spilled over to articulations about politics coming from celebrities—Angel Locsin, Catriona Grey, Liza Soberano—is no surprise. After all, the last thing a tyrannical, violent government wants is for personalities with millions of followers on social media to be talking about human rights or other national issues. Yet attacks on women’s articulations, artistic and otherwise, did not only happen during the Duterte years. An important case to mention is that of Nora Aunor, who was awarded National Artist by her peers twice across the Aquino and Duterte governments, but was denied the award by both Presidents. The premise of the denial was the analysis of Aunor’s person as someone who cannot be a role model for the youth, given her history with purported drug use. It of course didn’t matter that being a role model is not a requirement for becoming a National Artist.

This is why censorship can only be a conundrum in a landscape like this one. While culturally, we see changes in the ways people live and speak, and we have witnessed an evolution in the manner in which we talk about sex, violence, and politics, institutionally—both in government, the Catholic Church, and civil society—what still dominates is a very backward sense of what the public should be allowed to see, and how creative output should always be at the service of certain beliefs and morals.

That this is subjective is precisely the point. In a country where there are no clear rules or limits, where there is no list of banned words or subjects, no law that says certain content and portrayals are disallowed, it is easy to imagine that this is proof of our democracy and freedom. And yet what this research reveals is that the lack of limits on creative freedom does not mean censorship does not exist; it means that acts of censure can come from anyone at all, on every subject matter, portrayal, or practice that is deemed as wrong or offensive by the next person or institution. Here, it is not a matter of what’s not allowed, but what is offensive; not a matter of what we cannot talk about, but who, and how many, are offended.

In this landscape that brands itself as democratic, this is what censorship looks like: it is without limits.

Katrina Stuart Santiago is a writer and cultural critic from Manila, with a 15-year writing practice across mainstream and fringe publications, in print and on digital. Her creative practice has fueled her activism, which cuts across issues of cultural labor, systemic dysfunctions, and institutional crises, and how these are tied to bigger issues of nation and governance. She is founding director of small press, bookshop, and gallery Everything’s Fine, co-author of UNESCO-Germany's Fair Culture Charter, and collaborator of the Feminist Journalist Network of the Association for Women in Development. She heads the civil society organization People for Accountable Governance and Sustainable Action-PAGASAph that seeks to provide the space for political action from younger civil society actors, and was 2023 Public Intellectual of the Democracy Discourse Series of the Southeast Asia Research Center and Hub of the De La Salle University. Through Everything's Fine she is constantly redefining her practice as an independent cultural worker, as she nurtures communities that seek safe, kind, and productive spaces for difficult conversations and relevant dialogue. She writes at katrinastuartsantiago.com and is @radikalchick online.

- Katrina Stuart Santiagohttps://radar.artsequator.com/author/katrina-stuart-santiago/

- Katrina Stuart Santiagohttps://radar.artsequator.com/author/katrina-stuart-santiago/

- Katrina Stuart Santiagohttps://radar.artsequator.com/author/katrina-stuart-santiago/

- Katrina Stuart Santiagohttps://radar.artsequator.com/author/katrina-stuart-santiago/

Similar Reads