cw: Contains mentions of suicide

There appears to be more local books and writing about mental health in the Singapore lit scene in recent years.

In Mahita Vas’ book A Good Day To Die: Inside A Suicidal Mind, published this year, she details specific issues of discrimination in Singapore, such as being rejected by all of the major insurance agencies on account of her mental condition. In 2019, readers were floored by Loss Adjustment, Linda Collins’ personal account of the loss of her 17-year-old daughter Victoria to suicide, and how she struggled to seek answers from school teachers and counsellors, throughthe pages of her daughter’s diary. And looking specifically at a period between 1961 and 1994, Danielle Lim’s 2016 book The Sound of Sch: A Mental Breakdown, A Life Journey was an intimate examination of mental illness and caregiving in Singapore.

Titles like these mean that we now have more access to Singapore writing on the mental health and issues that are particular to the local context, which gives light to a topic that has traditionally been seen as–and perhaps still is–taboo. These books are often not easy to read, and I can only imagine how much harder it would have been to write them. With more local literature on this topic, it is therefore important at this time to also consider the role and responsibility of editors and publishing houses in supporting such efforts. How do they build the space to empower more writers to do work that is deeply personal, and can be at times triggering or traumatic? What does such a ‘safe space’ look like within the broader literary ecosystem?

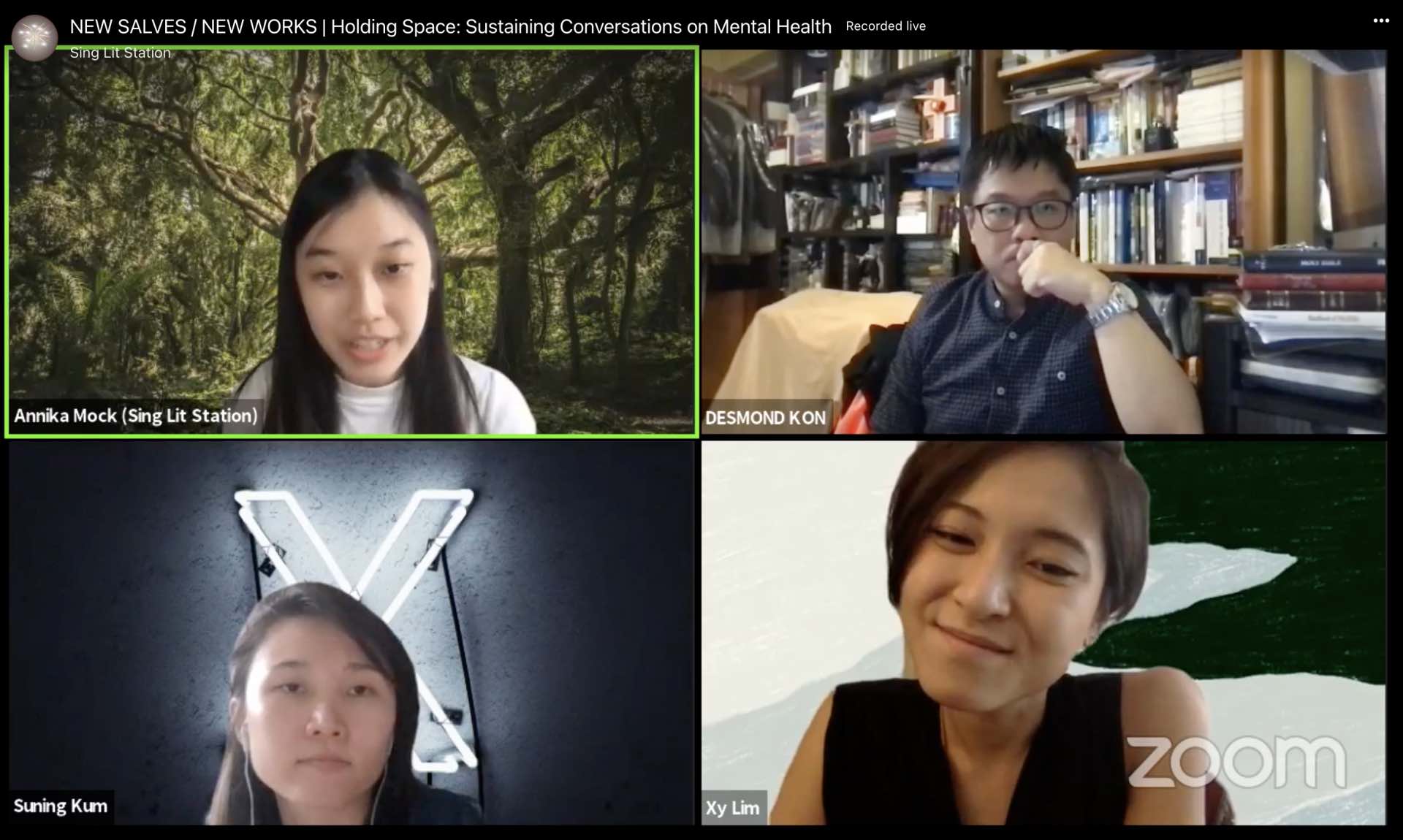

Local literary non-profit Sing Lit Station organised two Facebook panels in October this year, specifically delving deeper into the experience of writing, editing and publishing mental health. In the first panel ‘A Spoonful of Sugar: Writing as Medicine’, Lim and Vas were joined by Ang Shuang, whose debut work How To Live With Yourself is currently available for pre-order, to share about the journeys they have with their recently published works on mental health. The second panel, ‘Holding Space: Sustaining Conversations on Mental Health’, saw editors Xiangyun Lim, Suning Kum and Desmond Kon speaking more on the challenges and nuances of supporting and promoting the writing of and around mental health.

Shuang, a younger voice within the Singapore literary (or Sing Lit) landscape, shared in the writers’ panel that she started writing because of all the writers who had come before her and “put into words” an experience that she had gone through herself: “That is why I also wanted to write, to connect more bridges, to make people feel less alone.” Something that stood out was how all three writers also spoke very much about how Singaporean literature helps to give voice to an illness still very much lived in silence in this country. For example, after her book was published, Lim received messages from friends and family who shared that they were going through similar journeys, and how her book helped them understand and process what they were going through.

In the second panel, the editors also acknowledged the importance of holding space for writers to share honestly and authentically about their personal journey. Writer and editor Kon rightly highlighted the specific sensitivities required in publishing and writing on mental health: “We have to be very careful, because sometimes these writers are still right in the midst of the pain and processing it. So we do not want to be the trigger.”

Kum, editorial manager at Ethos Books, shared an account of her editorial process with Lim in publishing The Sound of Sch: “I would always preface a lot of my comments with acknowledgement and affirmation.” At the post-panel Q&A session, Collins, who also worked closely with Kum, acknowledged with appreciation how enabling such safe spaces was crucial to the creation of Loss Adjustment.

I had a separate conversation with Shuang and Vas, where they elaborated on the relationship between writers and editors, reiterating the importance of cultivating “safe spaces” from the start. This involves a consciousness and intention on both parties to have an honest conversation about the writer’s needs, and also discussing boundaries from the very beginning. “It is crucial to understand why we want to tell a certain story, and to keep to those goals in the editorial process,” said Shuang. What then is the key to cultivate this “safety”? Both authors answered unanimously: “Empathy.”

A deep, contemplative silence hung in the room for a moment as the gravity of the word sank in. I couldn’t help but also reflect on how I had been conducting the interview thus far – had I been empathetic? Had I practised the capacity to hold the discussion from within the writers’ frame of reference? Had I been actively cultivating and maintaining that “safe space” for the writers to talk about their work? How often do we take for granted the personal stories that are shared so vulnerably and put out on shelves for strangers to read?

Extending from these questions, I also wondered about how empathy may look like in a relationship between a publisher and writer. Commenting on the delicate balance editors need to tread between giving constructive criticism and preserving the truth and authenticity of the writers’ personal accounts, Vas said: “You have to understand that (mental health) is a very difficult subject to write, and if you want something changed, think about why you are asking that. Is it important? Is it necessary? Does it make the book better or is it just your own opinion?” Shuang added: “Unless it is a comment about technique, or how the audience may read or perceive it, I don’t think that editors should be changing content”.

Xiangyun Lim, editor of White: Behind Mental Health Stigma echoed these thoughts in the second panel. She shared her experience of working closely with all 50 contributors of the book, anchored by her key belief in consistent communication and always returning to the integrity and authenticity of the contributors’ narrative: “We have to understand the narrative they want to tell, and what is the narrative they would like to grow into because not everyone wants to be defined by their experience.”

Publishers also hold the responsibility to not sensationalise the topic in the publicity process, but to instead focus on the systemic issues of mental health which the book is bringing forth. “While there is a need for publicity, as publishers, we go through these plans with the authors. I think it is important that authors understand that they can say no to certain publicity tactics or strategies,” said Kum during the second panel. In publicising Loss Adjustment for example, Kum and her team were conscious to make sure that there was someone familiar with Collins each time she had an interview. It takes sensitivity to publicise the writing, while giving care to the writers who are resurfacing and reliving the trauma again in the process.

But where do publishers draw the line when it comes to caregiving for authors? Kon gave a real and honest picture of how overwhelmed anthology publishers in particular can get. When receiving hundreds of submissions daily, it becomes almost second nature to send out standard rejection letters which can come across as cold. But should aspiring writers learn to accept that as part of industry practice? Or should publishers at least try to “sound humane” in these ‘standard’ rejection letters to protect new voices and writers emerging from pain? Underpinning all of this, is it necessarily the responsibility of publishers and editors to uplift and empower writers?

For Vas, care ultimately has to come from self. She shared, for example, that the responsibility lies within the writer to know when to stop and “take a break” from writing when it gets too overwhelming. Lim also added that “the journey has to begin inside ourselves… before we can take it out to the world. If not, it is going to be terrible and traumatic.”

One thing I have learnt from these writers and publishers is that mental health recovery is not a linear journey – it is disorganised, and can get messy. Perhaps so is the process of writing and publishing it, as we all learn and grow together as a literary ecosystem. There is no perfect formula or a “how-to” guide when it comes to the practice of care towards artists and writers when dealing with mental health subjects. Discussions like these organised by Sing Lit Station are definitely important to help all of us better understand the role of various players within the Singapore literary ecosystem. This invitation to peek behind the veil is also part of demystifying the discourse around this very important topic, which has stayed silent for too long.

A Spoonful of Sugar: Writing As Medicine and Holding Space: Sustaining Conversations on Mental Health both took place online on 17 October 2021, as part of programmes by Sing Lit Station. Sing Lit Station is a literary non-profit and writers’ centre in Singapore. Support them here.

Sarah Tang is an independent arts writer, dramaturg and producer, with a special interest in working across various disciplines and mediums. Her practice centres around creating avenues for dialogue through art, and she believes in the power of collaborating with stakeholders across sectors to effect positive social change through the arts.