There is very little to no publicity when it comes to arts censorship in Vietnam. With the infrastructure for arts journalism still in its nascent stage, only certain cases of censorship occasionally garner interest from the media. In researching and interviewing people for this article, I found that there were many anecdotal cases, but few were able to go on record formally, making verification difficult.

These incidents happen without any public discussion, but instead with tacit acknowledgement, as an exhibition opens with a switched-off TV screen, a blank wall, or an empty pedestal. Informal discussions then take place within the community in the form of speculative murmurs on why the work, or its creator, or both, were being challenged. Frustration about the absurdity of the situation will spurt out, but then everyone moves on. It’s just another day here. There is nothing one can do except show solidarity, or offer an alternative way to show the removed work. Despite various creative efforts that do occasionally prove that David can triumph over Goliath, it is dreadful to work under an environment governed by ambiguity, suspicion, and paranoia, where one is always staying alert for that unexpected knock on the door.

Exhibition Licence: To Apply or Not to Apply

Under the Decree 23/2019/ND-CP for Exhibition Activities by the Vietnam government, all fine art and photographic exhibitions are required to apply for a licence. In theory, the procedure for this and what constitutes prohibited content appear somewhat straightforward, but in practice it proves otherwise. In order to legitimise an exhibition, one has to submit a request for licence, which has to include images and detailed written descriptions of all works being shown. For national exhibitions, the application is done to the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism; for individuals and local organisations, it goes to the Department of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

Most registered arts spaces in Vietnam apply for the exhibition licence, while artist-run spaces or commercial galleries that exist as a “shop” on paper usually don’t. For the latter, organisers are mindful when promoting their events: opting to either call them “presentations” instead of “exhibitions”, or to not indicate the format of the event at all. Meanwhile for registered arts spaces, the process is tedious and antithetical to some extent, as besides the application, organisers must submit full transcripts in Vietnamese for film, video, and sound works to the Department of Information. Sometimes, works are denied a license not because of the content, but their length — examiners not being able to make time for a twelve-hour looped video, for instance.

Under Clause 8 of the Decree 23/2019/NĐ-CP for Exhibition Activities, several types of content are strictly prohibited: those that advocate against the government, instigate war and conflict amongst ethnicities, falsify historical facts, disclose an organisation’s secret without having its consent, or violate civilised lifestyles.

Still From Placebo (2019) by Phan Anh. Image courtesy of the artist.

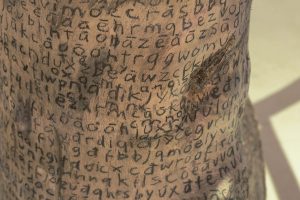

As transparent as this seems, at times artists are still left baffled when their works are not allowed to show. For instance, a low-resolution video-documentation of a durational performance, where the artist carves unintelligible strings of letters on tree logs was deemed unsuitable, as it might exert an unhealthy influence on the youth. Footage of actual protests and strikes that have circulated online are considered sensitive, polarising content that threatens national unity. There have been complaints that the government officers in charge of assessing and licencing artworks are not equipped with fundamental knowledge on art and cultural activities.

However, after a period of “working together”—how organisers often describe the interaction between them and the licencing body—both parties seem to be moving one step closer towards a common ground, with the process being less rocky, waiting times being reduced, and sometimes, unofficial verbal agreement being given.

Alas, securing the licence does not guarantee that the show can go on, since there is another stakeholder involved: the cultural police from the Department of Public Security. Undercover cultural police make unannounced visits to the exhibition site, which many times results in the removal of works, or even the cancellation of the show. At times the police might manage to identify unlicensed versions of artworks, while at other times they might demand for a re-examination of a work or even an entire exhibition, despite the Department of Culture, Sports, and Tourism having given their approval. These surprise visits have caused great ordeals, and over the years, experienced organisers have developed a special skill in identifying plainclothes officers among exhibition-goers, just by their appearance.

Creative Tactics to Survive

Since there is no possibility of changing the policy, cultural workers often take matters into their own hands with creative tactics, or what artist-curator Bill Nguyen describes as “the power of editing” in our previous conversation. While in most contexts “editing” is the act of modifying, condensing, and rearranging words so that a text appears more coherent, here it refers to a required skill when preparing the request for an exhibition licence: making sure the exhibition’s message and the content of the works is succinct and straightforward, and choosing to highlight arbitrary details that the organisers know will not attract unwanted attention from the licencing committee.

Editing also happens in the form of creating Vietnamese names for non-Vietnamese artists, as the licencing process is even more complicated when an exhibition has “foreign elements”. Editing proves its power when it gives the work a second chance at being visible, even if it is to a smaller audience through private screenings or secured online distribution. Some artists and organisers even make the act of censorship visible to the public as a statement–for instance, by leaving notes or covering the paintings instead of a clean removal–as a reminder of the state of freedom of artistic expression in Vietnam.

Nonetheless, as powerful and useful as editing might seem, it does carry the risk of self-censorship—whether consciously or unconsciously—as it becomes a standardised practice. Knowing what will and will not pass content screening, some organisers even advise artists to make adjustments to their works, or deliberately choose works that will not violate Clause 8 even before submitting the licence application. Some organisations also refrain from discussing politics or social issues in their exhibition material or on social media. Artists who are used to facing challenges from the authorities previously, knowing that their works will never be licenced, will often exhibit overseas but not in Vietnam.

Rooted in the intention of not getting anyone in trouble, these decisions are often viewed as inconveniences or small sacrifices towards the bigger picture of being able to present the work to the public. It is, however, exhausting, and even discouraging, for artists, curators, and arts managers to continue their practices under this constant fear. Such fear prompts practitioners to come up with different ways of coping, and in a way, this has led to the uniqueness of the local arts scene. But the flip side is the stifling of artistic expression, with many ideas receiving a death sentence before they can even materialise.

Linh Le

Linh Lê is an independent curator, writer and researcher from Saigon, Vietnam. Her work investigates the changing landscapes and ecologies of Saigon and other parts of Vietnam under the pressure of modernisation and urbanisation, while at the same time exploring and filling in the gaps in contemporary art historical discourses in Vietnam, particularly in experimental art forms such as performance art and video art. Since July 2024, she has been working on Đo Đạc, a site-responsive curatorial project that attempts to survey the impact of forced resettlement in Thủ Thiêm peninsula, Sài Gòn. She is currently a Curatorial Board member of Á Space (Hà Nội), and a research fellow of ArtsEquator’s Southeast Asia Artistic Freedom RADAR project.

- Linh Le#molongui-disabled-link

- Linh Le#molongui-disabled-link

- Linh Le#molongui-disabled-link

- Linh Le#molongui-disabled-link