The Asia Europe Foundation’s Culture360 and ArtsEquator present a series of 5 co-commissioned articles that look at arts groups, artists and performances in Southeast Asia that are comprised of or address artists with disabilities. In this article, Mark Louie Lugue meets Filipino artist Nolet Soliven and his wife Tosh, to talk about Nolet’s practice, and the challenges he faced after his stroke a few years ago.

It was an early morning in 2013 when Tosh Soliven, the wife of Filipino artist Nolet Soliven, received a text message from their housekeeper. Her husband was already asking to be fetched from his studio. She found this odd, as oftentimes, Nolet himself would call her. Upon her arrival, she found her husband struggling to descend the stairs from his second-floor studio. Nolet couldn’t move his body properly then, and his speech was slurred.

They brought Nolet to the hospital. “It was a massive stroke,” Tosh explained. Nolet quickly underwent an operation and spent three days in a coma followed by a couple of weeks in hospital, before returning home, bedridden for the next few months. “Angels,” Tosh said, recalling how her husband survived the events leading to his stroke.

The stroke left Nolet’s right body paralysed, and his language abilities affected severely. Aside from his initial inability to open his mouth to speak, he was also facing difficulties pairing images with words in his mind. When asked to draw an apple, he was unable to translate the word ‘apple’ into a ‘drawing of an apple’, even if he recalled how an apple looked like. Picking up his paintbrush again was a huge challenge to surmount.

“He has always dabbled in art; he always loved to draw,” Tosh reflexively answered when I asked about her husband’s personal and artistic life prior the stroke. Even if there weren’t any upcoming exhibitions, he would draw and paint every single day for hours, consistently, on any possible material – from rags to used paper with written grocery lists.

Nolet pursued a degree in Fine Arts in the University of the Philippines–Diliman, where he studied under the tutelage of Nestor Vinluan and Roberto Chabet – big names in the Philippine art scene – who had, early on in his career, influenced his creative philosophy and process.

Then, Nolet taught photography and drawing at the University of the Philippines in Baguio, a city in the mountains of Cordillera, north of Manila, where he and his growing family stayed for eight years. Openness and dialogue were important aspects in the artist’s teaching style. In class, he would treat his students as peers. In fact, from time to time, they would stay over at his place, discussing art over friendly drinks all night long.

Although more known as an abstractionist, Nolet worked on both figuration and abstraction. He would always draw and paint figurative nudes and parts of the body, as if in meditation, as he conceptualised what abstract painting he would work on next.

His abstract works steadily minimised the subject matter to strokes of thick paint. “It turns out this is a natural thing,” he jotted on one loose bond paper, referring to his tendency to paint abstraction. He continued, “when you get yourself more and more into expressing this visual language, you’ll eventually look outside of reality.”

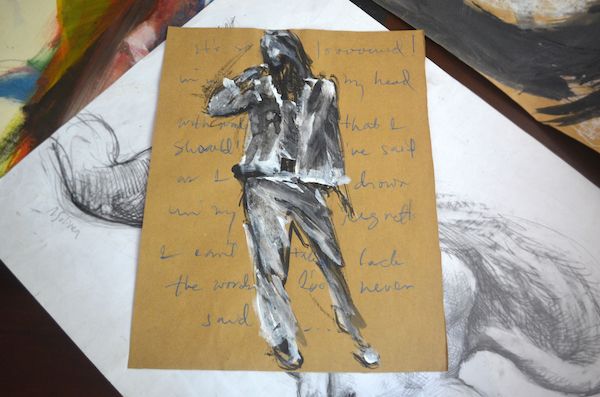

From time to time, he introduced words and sentences into his works, providing the viewer with a glimpse of how his mind worked on a specific piece. The captions present the raw thoughts and emotions of the artist as he delved into a better understanding of himself through his art. The gesture of integrating words into his art culminated when he and his former student, Sherwin Villano, put up a two-man exhibition of their painted works inspired by seemingly random words they gave each other.

His practice involved the use of words, whether it be through adding text to the work to explain himself or to use words as the springboard to his actual artmaking, or even to discuss art with peers. The stroke, which impeded his ability to communicate with words, brought him to a major turning point in his life.

It was not without difficulty that Nolet’s condition has improved since the day of his stroke. Up until the writing of this article, Nolet was undergoing relentless therapy with the help of experts from a circle of friends and family. He performs activities to recover his physical, language and artistic skills.

After the stroke, he could barely move his entire body, but after some rigorous therapy, he was able to move his left body more freely, allowing his dominant left hand to pick up his paintbrush again. Along the process of recovery, he gained a renewed eye for color. He shifted from a pale and monochromatic palette to a bright and vibrant one. His control of his brush is still evident in the “pixels” prominent in his most recent abstract series.

He may not yet be able to formulate sentences with finesse, but he can now express himself using several words he can muster. Although his physical condition prevents him from achieving the level of skill he once had, he has achieved significant progress in depicting figures.

Central to Nolet’s recovery is the steadfast support he receives not only from external groups, but from his family and friends. One remarkable support he gained through merit was a grant from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation – an American organisation established through the generosity of abstract expressionist painter Lee Krasner, the widow of Jackson Pollock – which helped finance Nolet’s further artistic pursuits and medical expenditures. Also, throughout the years, Nolet remains to be managed by Karen Koh of ArtsCura Singapore, an unfaltering benefactor, and a great friend.

Another is the government of the Philippines, which provides support to peoples with disability through discounts off medical expenses, and other goods and services. Nolet’s family highly appreciate this, given the amount they spend on his continuous medicine intake. However, Tosh laments the lack of better infrastructure in the country that provides access, specifically to parks that may help with Nolet’s recovery.

Lastly, Nolet’s family ensures that enough attention is provided for the success of Nolet’s recovery. Living in a compound with their relatives helps in big ways, as they experience no absence of support from the people around them.

At present, Nolet and Tosh are looking into putting up another exhibition any time soon. Also, they are in search for a more accessible studio, to allow Nolet the freedom of space as he continues his routine therapy.

At the latter part of the interview, Tosh brought in a huge case of works, allowing me to view them at my own pace. In the rich stash of perhaps never-been-seen works completed prior his stroke, I found myself fixated on a simple scribbled figure on a humble craft paper, inlaid with text written by Nolet: “It’s so loud in my head with words that I should have said as I drown in my regrets. I can’t take back the words I’ve never said.” Reading this sentiment as a foreshadowing of the unfortunate event has stirred inside me an ironic mingle of sorrow and hope. Although it will take time before Nolet can fully express himself again through words, there is no better time than now for him to do what he does best – to allow his art to speak out loud on its own – for his art to speak beyond words.

About the author(s)

Mark Louie Lugue is an independent writer and curatorial practitioner from the Philippines. At the same time, he is a graduate student, taking up Art Studies in the University of the Philippines. His writings can be found in his blog, ManilaArtScene, an online platform that primarily showcases the local art scene in the Philippine capital. Follow it via Facebook and Instagram.